Chapter 18, Ophis And The Serpents

Introduction | Chapter I. Shiva | Chapter II. Baal | Chapter III. Buddha | Chapter IV. “The Wisdom of the Other Bank” | Chapter V. King Asoka | Chapter VI. The Mahâyâna | Chapter VII. Avalokitishwara | Chapter VIII. The Cave Temple and its Mysteries | Chapter IX. Architecture | Chapter X. The Essenes | Chapter XI. The Essene Jesus | Chapter XII. More Coincidences | Chapter XIII. Rites | Chapter XIV. Paulinism | Chapter XV. Transubstantiation | Chapter XVI. Ceylon | Chapter XVII. Alexandria | Chapter XVIII. Ophis and the Serpents | Chapter XIX. Descent Into Hell |

Serpent symbol everywhere in Shiva-Buddhism—Unknown in early Buddhism—Legend of Buddha burning the palace of the Naga king—On a bas relief of the Sanchi Tope—The Serpent and the Lotus leaf—Valentinus—Dhyâni Buddhas—Saktis or Wives of the Dhyâni Buddhas—Gnostic Aeons—They also have their Saktis—Violent attack of Tertullian on these Saktis—Tertullian and Fourth Gospel—Valentinus and Serpent Worship—The Gnostic Kristos a Serpent—Cainites and Naasseni—The "Thousand-eyed (Dasasatanayana)" in Alexandria.

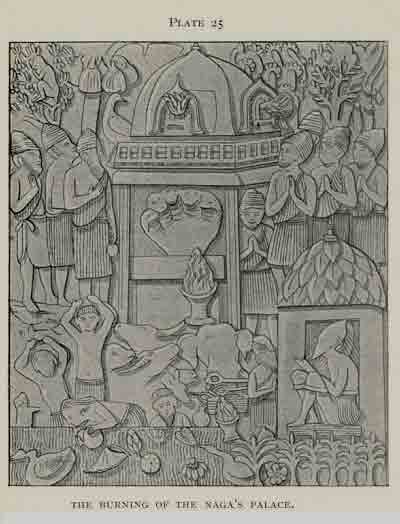

In Shiva-Buddhism the serpent symbol is everywhere; on the miniature Chaitya-domes, on the heads of Buddha, in all the temple sculptures, on the altar. It is a striking and immensely important fact that on the early topes, Sanchi and Bharhut, there is no Serpent worship. One exception is noticed in Mr. Fergusson's Tree and Serpent Worship. I reproduce it. (Pl. 25). This bas relief is to be seen at Sanchi. Sir Alexander Cunningham denies that it is Serpent worship, but Mr. Fergusson points to the altar, and he makes one very noticeable observation. The worshippers are not like the other Buddhists of the sculptures. They have different dresses and different caps. Mr. Fergusson calls them Dasyus.

I think if these writers had come across the legend of the burning of the palace called Nangewenodenneye in the Cingalese records, their conclusions would not have been antagonistic. I have given this story already. Buddha visits Samana Deva Rajah in his palace in hell. He frightens all his Nâgas to death by making fire issue from four sides of the palace. The Nâgas are the ancient rulers of Ceylon, and the Nâgas are to this day a sect of Shiva. Probably in early times it was a generic title. The five-headed serpent (Pl. 25) is the Serpent King, with his fire altar and crowd of bullocks and other victims, which include I fear, two little boys. There is wood piled, and a second brazier is in the corner. Buddha's object, we must recollect, was to secure the Minne Phalange, or "Seat of Supremacy." In one corner of the Plate is Buddha working his magic under a Pan-sil. The Kûsa grass mat of the ascetic was called the Throne of the Bodhi (Bodhi mandi).

The Fourth Gospel is judged by scholars to be much more recent than the other three. Irenæus calls it the Gospel used by Valentinus and his followers. He tells us that there were four Gospels used by the church; Matthew's, which was the Gospel used by the Ebionites; Mark's, the Gospel used by the Docetæ; Luke's, the Gospel used by the Marcionites; and John's, the Gospel used by the Valentians! Does this mean that each of the four principal sects had a version of the early Gospel, the "Gospel according to the Hebrews," and that these were each altered by them to suit their teachings?

Valentinus is placed by Matter at the head of the Gnostics.* He became prominent in the Church about A.D. 136 on the death of Basilides.†

In our last chapter we dealt with the distinction drawn by the Gnostics between the visible and invisible portions of the universe. Valentinus seems to have gone beyond Basilides, he made Buthos (the unmanifested portion) into a God. Now one section of the Indian Swâbhâvikas also worshipped a space turned into a God. The Prâjnikas, says Hodgson, made Nirvritti into a God. And the other section of the Swâbhâvikas went nearly as far. There was nothing, they said, but matter. It was called Swayambhu (the Self-existent).

The Mortal Buddhas who ruled this space in Shiva-Buddhism, were changed into Dhyâni Buddhas, that is, Buddhas that have never lived on earth at all. This was, of course, nonsensical, but the strict pantheism of the second school required all divine beings to descend in an unbroken chain from Îs’wara. Valentinus took over these Dhyâni Buddhas, and called them Æons (Eternals). With both they were "virtues," "powers," "emanations." Also they increased and multiplied like mortals, for each had his sakti, or female energy.

I will give the names of the Five Dhyâni Buddhas. They helped Îs’wara to build up the universe.

Tertullian attacks these emanations of Valentinus, and their ever-increasing list, in the writings of Secundus and Marcus. He derides their "Fraternal nuptials,"* and their "conjunctions of execrable and unseen embraces"; and he makes much fun of the changes in conditions and alterations of domicile of the various beings, human and divine, at the end of an age—Achamoth restored to the Pleroma; the "Demiurge" promoted from the celestial Hebdomad to the higher regions"; and the just of the earth dispersed amongst the angels"—without anyone being allowed to carry away any of the matter of the earth for a body.† Does he not picture here the constant shuffling of cards in the Ceylon Pantheon, and remind us that in the Mahayana there are at least seventeen distinct Devas who each created the world? "With humorous irony," as the two clerical translators put it, Tertullian describes how a "wonderful puppet," Soter (the Saviour) is formed out of these Gnostic emanations, although St. Paul practically says the same thing. Tertullian specially attacks the gross deeds of "Sophia" and "Achamoth" called "left-handed" deities‡ he tells us. Noteworthy is the fact that with these Gnostics Soter the Saviour had three natures: the carnal or left-handed; the right-handed balanced between the carnal and spiritual; and third, the spiritual.* This seems to show that the differentiation between the active god and the Unmanifested Supreme, or as Tertullian puts it, the "placid" and "stupid" divinity,† was not as closely insisted on as it is now. Padmapani wears his mask loosely, and allows Trailinga Î'shwara's head to peep out. Serapis was also called Soter.

Although the Buddhists and Gnostics differ in the choice of the virtues and qualities with which they christen their Æons and Buddhas, the analogy between them is sufficiently close.

Is there anything like all this in the Gospel that, according to Irenæus, was viewed at one time as the Gospel of Valentinus.

"No man hath seen God at any time. Monogenes, who is in the bosom of Propator, he hath declared him" (John i. i8).

Propator is "The Father" of the Fourth Gospel, and according to Matter, Proarche (the Beginning) is another name for him. Then we see that Monogenes made the world (John i. 3). He is the Phos, who lights up the Pleroma, as Padmapani lights up the Pravritti (John viii. 12). And the names of other Æons, Zoe, Aletheia, Logos, Ecclesia, figure in the narrative.

Now this seems the teaching of Valentinus in epitome,‡ but here comes a bewilderment: Neander calls St. John's Gospel an attack on the Gnostics.

This is a little remarkable. According to Irenæus, Valentinus at one time believed that this gospel set forth his philosophy and teaching, and yet at a subsequent time a writer, not without shrewdness, can see nothing in the gospel but a fierce attack on Valentinus. It seems plain that these two observers cannot have seen the same document—or at any rate, the same document in the same condition.

Did Valentinus know anything of Serpent-Worship?

Irenæus declares that he held that the mighty Sophia, the Dharma, the Wisdom of the Gnostics had for mother the Serpent Ennoia, and for father Buthos, the void.

Ennoia brought forth two emanations—one perfect, the Christos, the other imperfect, Sophia Achemoth. She descending into Chaos lost her way, and became ambitious to create a world entirely for herself.

Sophia, as I have said, parented Ialdabaoth, and Ialdabaoth parented Ophiomorphus, who had six sons:—Sabaoth, Adonai, Eloi, Oraios, Aslaphaios, Iao.

"Ophis," says Matter, "was at once with the Ophites both Satan and Christos."* The Pneumatics cited John iii. 14, 15, to prove the identity of the Saviour and the Serpent Ophis.† "Serpentem magnificant intantum ut ilium etiam Christo prœferant," says Tertullian.‡ The Ophites outdid the serpent petting of Nâgpur in India:—

"They bred in their sanctuaries living serpents, and these were so trained that during the celebration of the Holy Communion these creatures issued from their cages, and came and "blessed" (by licking it) the consecrated bread exposed on the holy table."§ When the Ophites and Marcionites joined forces, and no live serpents were available, they had to be content, according to Theodoret, with a brass serpent in their churches.+

Amongst the Gnostics there was a good serpent and also a wicked serpent. The Sethians and Paratæ worshipped a good Serpent. The Cainites worshipped an evil Serpent, and so did the Ophites, according to Matter, but Hippolytus identifies the latter with the Naasseni who professed to have received their teaching from James, the brother of the Lord. They held that "Jesus" represented three principles, the angelic, the psychical and the earthly, in fact that he was apparently Trailinga Î'shwara. Here is another curious point. According to Hippolytus the Naasseni and Phrygians called the Father "the many named, thousand eyed, Incomprehensible."* Here we have Dasasatanayana's name literally translated. Shiva as Sesh is the "thousand-eyed" (Dasasatanayana).

Here is a passage in a hymn of the Naasseni:—

"Evoe, evan! Thou art Pan as thou art Bacchus, as thou art Shepherd of brilliant stars."†

The Shepherd of the brilliant stars must be Shiva as Sesha, the shepherd of the spangled serpents in the sky.

Also Shiva is the Bacchus and Pan of the Greeks.

Suggestions for Further Reading

- Hinduism and Christianity, Jesus in India

- The Advaita Vedanta - Non Duality

- Introduction to Hinduism - Prakriti

- The Kapila And The Pâtañjala Samkhya Yoga

- Brahman According to Advaita and Dvaita in Hinduism

- Atheism and Materialism in Ancient India

- Solving the Hindu Caste System

- Emptiness or Sunyavada in Buddhism

- Buddhism - A Discourse on Ignorance

- The Working of Maya or Illusion - A Buddhist Perspective

- Buddhism - The Middle Way or the Middle Path

- What Samsara Means in Buddhism

- The Chaos Theory and Nirvana in Buddhism

- Hinduism and Caste System

- Dealing with Chance, Fate and Acts of God

- Death and Afterlife in Hinduism

- What is Hinduism?

- Hinduism and Diversity

- Hinduism and Judaism

- Hinduism and Same-sex Marriage

- Significance of Happiness in Hinduism

- Redirect - Symbolism Hinduism

- The Meaning and Purpose of Yoga

- Essays On Dharma

- Esoteric Mystic Hinduism

- Introduction to Hinduism

- Hindu Way of Life

- Essays On Karma

- Hindu Rites and Rituals

- The Origin of The Sanskrit Language

- Symbolism in Hinduism

- Essays on The Upanishads

- Concepts of Hinduism

- Essays on Atman

- Hindu Festivals

- Spiritual Practice

- Right Living

- Yoga of Sorrow

- Happiness

- Mental Health

- Concepts of Buddhism

- General Essays

Footnotes

276:* Matter, "Hist. du Gnosticism," II., p. 37.

276:† Ibid, II., p. 38.

278:* Tertullian, "Adversus Valent.," VII.

278:† Ibid, C. XXXI.

278:‡ Tertullian, Ibid, C. XXV.

279:* Ibid, C. XXV.

279:† Tertullian, Ibid, C. VII.

279:‡ That is the opinion of Tertullian ("Adversus Valent.," C. VII).

280:* Matter, "Hist. du Gnosticisme," Vol. II., p. 152.

280:† Ibid, Vol. II., p. 163.

280:‡ "De praeser," p. 250.

280:§ Matter, "Hist. du Gnosticisme," Vol. II., p. 375.

280:+ Ibid, Vol. II., p. 395.

281:* Hippol., "Haer," v. 4.

281:† "Hippol. Haer," v. 4.