Relax With Yoga

Disclaimer: Information presented here is for information and educational purposes only and not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any condition or disease nor to be relied upon as a substitute for your own research or independent advice. YOU SHOULD ALWAYS SPEAK WITH A HEALTH CARE PRACTITIONER OR A SPECIALIST IN THE SUBJECT MATTER BEFORE TAKING ANY ACTION. No responsibility is accepted for any errors, omissions, or misleading statements on these pages or any site to which these pages connect

Yoga should always be practiced under the personal guidance of a qualified and experienced teacher to avoid injury. - Hinduwebsite.com

CONTENTS

1. THE ORIGIN OF YOGA

The basic problem of every living creature is survival in a hostile world. Countless generations ago, from the teeming human masses of the East, where man lived in ever-present dread of famine, disease, flood, invasion and vengeance of the gods, Yoga, a system or method of attaining physical and mental serenity under adverse and even horrible conditions, was introduced.

Man, in his essence, has changed little in the course of historic time. The philosophy of Yoga and its practice, which enabled the Indo-Aryan to survive the stresses of his time, can also enable people of the modern Western world to achieve contentment and security in the face of the cold war, the hydrogen bomb, missile, counter-missile and counter-counter-missile and other perils in a rapidly changing world.

Scholars who have attempted to trace the beginnings of the practice of Yoga have found that its principles were well established as far back as the time when the written word was new. There are many "books" of Yoga among the oldest scripts in Sanskrit, the ancient sacred language of India. Even these refer to a distant past in which the secrets of Yoga were passed on from generation to generation by word of mouth. Only the Indian form of Yoga is well known in

[paragraph continues] America and Europe, but there is strong evidence that Yoga principles were known to the Egyptians and Chinese and that there were monastic societies among the Hebrew Essenes who were, from reliable historical evidence, groups of Yoga practitioners. Perhaps the recent discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls will reveal some of the secrets of this philosophy that have been lost in the shadows of the years.

What Is Yoga?

The word "Yoga" cannot be translated into English. In the Sanskrit, it derives from the root "Yuja," which is to join or weld together. Just as two pieces of metal are welded together to become one, so in the philosophy of Yoga, the embodied spirit of the individual becomes one with the Universal Spirit through the regular practice of certain physical and mental exercises. In another definition, Yoga is the art of life and its philosophy is meant to furnish the principles that justify and explain that art.

One of the Sanskrit texts, the Bhagwad-Gita, describes Yoga as equanimity of mind which results in efficiency of action. For those to whom Yoga represents a religion as well as a way of life, Yoga means the union or linking together of man with God, or the disunion or separation of man from the objects of physical sensation in the material world. It is the science or skill which leads the initiate by easy steps to the pinnacle of self-realization.

There are many common misconceptions which stand between the truths of Yoga and those who live in the Western world. Many Americans have heard more about Yogis, or those who practice Yoga, than about Yoga itself. They picture the Yogi as an Indian fakir, swathed in rags, who spends his life on a bed of nails or sits motionless underneath

a tree until birds build nests in his hair. Their knowledge of Yoga is gained from supposedly esoteric literature or from side-show performers billed as "Swamis" or "Yogis" who stick pins through their flesh or permit themselves to be buried alive. More charitably, they may think of the Yoga convert as some mildly eccentric individual who enjoys standing on his head before breakfast.

Nevertheless, the true spirit and practice of Yoga has already spread to this country and has achieved what might be called a high degree of respectability. A number of colleges and universities, including such institutions as the University of Southern California, offer courses in Yoga. Also, such prominent athletes as Parry O'Brien, long-time holder of the world's shot-put record, have studied and practiced Yoga. It has spread even to the halls of our national Congress where Representative Francis P. Bolton's practice of Yoga has received nationwide press coverage. Stripping the "magic" from Yoga reveals that it is a practice that effectively enables its user to meet the stresses of modern life, and offers relaxation that may stand between its adherents and the stomach ulcers or psychiatrist's couch that are so common today.

You need not retire to an "Ashram," or Yoga retreat, to acquire the benefits of this system; rather, you can attain the serenity and relaxation that it affords through the information in this volume. Practicing Yoga takes but a few moments a day, although Yoga itself gradually fills the entire day of the person who pursues it with faith and belief.

2. CONTROL OF THE BRAIN AND NERVOUS SYSTEM

To attain a condition in which the fullest relaxation is possible, it is essential to control the brain and the nervous system. In old Sanskrit tracts we find the statement: "When the nervous system is relieved of all its impurities, there appears the perceptible signs of success ... the glowing color of health."

While speaking of the "brain," we must, to some extent, drop the Western traditional concept of the brain as the sole seat of consciousness. As far back as 2,500 years ago, the Yogins were in conflict with the accepted Hindu medical science of the time. These ancient medical men held, as did the ancient Greeks, that the heart was the seat of consciousness. The Yogins, on the other hand, stated that the brain, with its highly involved nervous system, was one unit which represented the true physical medium of human mental activity. There is an interwoven cerebro-spinal system and an autonomic nervous system. In the Yoga system of histology, the cerebro-spinal system is said to consist of the sahasradala, the brain, and the susumna, the spinal cord, which are enclosed within the cavities of the cranium and the spinal cord

or vertebrae. Linked together in the autonomic nervous system is a double chain of ganglia which are situated on each side of the spine and which extend from the base of the skull to the tip of the coccyx.

There are seventy-two thousand nadis, or nerves, which form a countless number of nerve endings. Of the nadis, about a dozen have been thoroughly studied by the Yogins. Three have been found to be of primary importance: The ida, or left nostril, the pingala, or right nostril, and the susumna, the spinal cord. These are believed to exercise control over voluntary and automatic responses of the human body and can be brought under control by Yogic methods.

Centuries before the recognition of electrical force by scientists, the Yogins had evolved a theory of nerve-impulse transmission which has won acceptance from Western medical investigators in this century. If we substitute the word prana for electrical impulse, we find that the oldest Yoga principles of neurology are now endorsed in the modern theory of nerve action. We can now understand that the Yogins anticipated the principles of electrical phenomena by discovering the positive and negative animal-magnetic currents which are the nerve impulses and which may be controlled and adjusted by Yoga practice.

The physical and mental well-being of every individual depends on the fine adjustment of the nervous system which controls even the secreting glands. One of the benefits of a Yoga regime is the control or restraint of the various modifications which may take place in the nervous system. In addition to the beneficial effects of the physical aspects of Yoga on the gross and finer muscles and tissues, it also establishes, through the postures and attitudes and psycho-physiological practices, complete control over the nervous system.

[paragraph continues] Only when the nerve impulses can pass in harmony through the spinal cord may samadhi, a state of suspended sensation, be reached.

Nervous Ailments

It is now fashionable to attribute many forms of disease to "nerves," which is a symptom, not a disease. Since the nervous system is in direct and intimate relationship with every part of the body, the slightest disorder in any organ registers upon the nervous system. Conversely, any serious nerve disorder will cause functional distress, and it is often impossible to disassociate the cause from the effect.

What we term "nervous weakness" is actually the response of a neglected or abused nervous system. The conditions that we lump together under the heading of "nerves" are merely the call of the nervous system for better care. Purification of the nervous system is possible through an improved mental attitude, rest, relaxation and recreation and the benefits of postures, or asanas, which adjust the tone of the spine and its components.

Some Aids to Mental Hygiene

Freedom from emotion is one of the tenets of Yoga. Early modern psychologists discovered a strong relationship between the emotions and the body in terms of increased or reduced ductless gland secretion, respiration, circulation and blood pressure. Yoga medical investigators have attributed diabetes, arteriosclerosis, nephritis and other diseases to the effects of emotion on the glandular system and thence on the body organs. Samatva, or absolute freedom from emotions, has been set as one of the prime essentials for the health of

the nerves and brain. Even a minor emotional flare-up or a long period of subdued anxiety will affect the body.

Concentration

A method of avoiding emotions and anxieties is to train or habituate the mind to concentrate on a chosen object. This concentration is called dharana. Without purposeful concentration, the mind diffuses its energies in varied directions, while with strong concentration, the mind can be freed of distractions and can approach a state of detachment or non-awareness of extraneous matters. This is the essence of concentration. The habit of concentration is known to produce a sedative effect, similar to that induced by deep breathing, with manifold benefits to the health of the nervous system.

The Need for Recreation

In India, a troubled individual is often able to retire for a while to an Ashram, or retreat, where he can live under the best possible conditions for the practice of Yoga and self-realization. (Note the use of the "retreat" by the Roman Catholic and other religions as a means to attain spiritual relaxation.)

One of the most depressing factors in the Western world is the monotony of occupation and the hectic pace required in almost every occupation or profession. In many cases, a change of occupation has effected radical cures in instances of nervous disorder, but this is not always feasible. However, any change in mental or physical occupation—and the change must be mental as well as physical—will add substantially to the health and tone of the nervous system.

Persons of sedentary habits will find relief in outdoor sports, such as mountain climbing, hiking, swimming, in addition to the practice of the Yoga exercises. For mental relaxation, the Yogins, whose troubled times were yet more calm than life is today, found their recreation in a mental state—in study and love of nature. By seeking unison with nature, they found that their entire beings were called into delightful activity with almost no effort of the will. They learned that the mind which lost itself in the love of nature found its nervous system refreshed, its vital forces renewed.

3. THE EIGHT PRINCIPLES OF RAJA YOGA

We will concern ourselves mainly with Raja Yoga, a system which has been found to be most applicable to the mental and physical conditions in which we live. Raja Yoga has eight principles. These are: (1) Yama—non-killing, truthfulness, non-stealing, continence, and non-receiving of any gifts; (2) Niyama—cleanliness, contentment, mortification, study and self-surrender to good; (3) Asana—posture; (4) Pranayama—control of vital body forces; (5) Pratyahara—introspection; (6) Dharana—concentration; (7) Dhyana—meditation; (8) Samadhi—super-consciousness.

Yama and Niyama constitute the moral training without which no practice of Yoga will succeed. As this moral code becomes established, the practice of Yoga will begin to be fruitful. The Yogi must not think of injuring either man or animal through thought, word or deed. However, this should not be extended to the limits to which the Jains of India carry it. Their creed forbids them to kill even an insect, and many never bathe lest by placing their bodies in water they may drown some creature living upon them. Yoga is logical. Its principles are not rules of magic that must be followed

without deviation, but general principles that expand to cover the exigencies of any situation.

Before continuing with our discussion of Raja Yoga, we should make a distinction between that school of thought and another, called Hatha Yoga.

Hatha Yoga deals entirely with the body. The sole aim of that school of Yoga is to make the body physically strong. For a strong body, however, you can achieve almost the same effects as those given by Hatha Yoga by enrolling in a gymnasium course at any muscle-building establishment. The exercises of Hatha Yoga are difficult and demand years of steady endeavor. Through this system, it is claimed that a Yogi can establish perfect control over every part of his body. The heart can be made to stop or go at his bidding and can control the flow of blood and the sensations of his nervous system.

The result of this part of Yoga is to make men stronger and to prolong their lives; good health is its one goal. From the point of view of the Raja Yogi, the person who perfects himself in Hatha Yoga is merely a healthy animal. This system does not lead to spiritual growth or give man the help to meet his need for relaxation which is found in Raja Yoga. However, certain aspects of Hatha Yoga have become part of the regime of Raja Yoga. These include some of its exercises, dietary aspects, and disease preventives, which provide the physical state of well-being which enables the proper pursuit of Yoga.

The exercises, or postures, are called asanas. These are a series of exercises which should be practiced daily until certain higher states are reached. They constitute the next stage in Yoga. At first, a posture should be adopted which can be held comfortably for a fairly long time. It has become

necessary to adapt the traditional Yoga postures to meet the needs of Western man. While there is no evidence of any physical or physiological difference between the people of the East and West, there are certain acquired differences.

Ours is a civilization in which much time, both at leisure and at work, is spent in a sitting position. In the East, the great mass of people are unfamiliar with the chair in its different forms. Theirs is what might be called a "squatting" culture. Hence muscular development from childhood on is along different lines. Postures in which the Indian naturally relaxes would be torture for the Westerner. The position which is easiest is the proper one to use.

You will discover later that in the carrying out of these physiological matters there will be a good deal of action going on in the body. Nerve currents will have to be displaced and given new channels. New vibrations will begin and the constitution will in effect be remodeled. The main part of the action will lie along the spinal column, so that it is necessary to hold the spinal column free by sitting erect and holding the chest, head and neck in a straight line. Let the whole weight of the body be supported by the ribs and in an easy natural posture with the spine straight. You will find that you cannot think high thoughts with the chest in. Such is the effect on the body of what we call the mind.

After you have learned to have a firm, erect seat, you should perform a practice called the purification of the nerves. In the words of one of the ancient scriptures, or Upanishads, "the mind whose dross has been cleared away by pranayama becomes fixed in the path of Yoga ... first the nerves are to be purified, then comes the power to practice pranayama."

The technique for this is as follows: stopping the right nostril with the thumb, with the left nostril inhale according to your capacity. Without pausing, exhale through the right nostril, while closing the left one. Now, inhale through the right nostril and exhale through the left. Practice this three or five times at four intervals of the day—on awaking, at midday, in the evening and before going to sleep. Within fifteen days to a month, purity is attained; then begins pranayama.

Practice is absolutely necessary. You may read about Yoga by the hour, but without practice, you will not make progress. We never understand without experience. You will have to see and feel this yourself, as explanations and theories will not do. There are several obstructions to practice. The first is an unhealthy body. You must keep your body in good health. Be careful of what you eat and drink and what you do. Always use a mental effort to keep the body strong. Keep in mind that health is but a means to an end.

The second obstruction is doubt. We always are skeptical about things we cannot see. You will naturally have doubts as to whether there is any truth in this philosophy. With practice, however, even within a few days, the first glimpse will come, giving encouragement and hope. A widely-quoted commentator on Yoga has written: "When one proof is realized, however little that may be, that will give us faith in the whole teachings of Yoga." If you should concentrate on the tip of your nose, in a few days you will begin to smell the most beautiful fragrance. That will be enough to show that there are certain mental perceptions that can be made without contact with physical objects. Remember, too, that these are only the means. The aim, the goal, the end of this

training is the liberation of the soul and freedom from tension and fear. You must be master of your surroundings. Nature or the world about you must not rule you. Never forget that the body is yours, you do not belong to the body.

Now, we may consider pranayama, or breath control. What has this to do with concentrating the powers of the mind? Breath is like the flywheel of your living machine. In a big engine you will find that the flywheel moves first and that motion is conveyed to finer and finer machinery until the most delicate and finest mechanism in the machine is set in motion. Breath is like that flywheel, supplying and regulating the motive power to everything in the body.

Consider that we know very little about our own bodies. We cannot know. Our attention is not discriminating enough to catch the very fine movements that are going on within. We can know of them only as our minds enter our bodies and become more subtle. To get that subtle perception, we must begin with the grosser perceptions, thus reaching the mysterious something which is setting the whole engine in motion. That is prana, the most obvious manifestation of which is the breath. Along with the breath, we slowly enter the body, which enables us to discover the subtle forces and how the nerve currents are moving throughout the body. When we perceive and learn to feel these forces, we begin to get control over them and the body.

The mind is also set in motion by the different nerve currents, bringing us to a state in which we have perfect control over body and mind, making both our servants. Knowledge is power, and to get this power we must begin at the beginning, the pranayama restraining the prana. As you follow this text, you will see the reasons for each exercise

and learn which forces in the body are set in motion. You must practice at least twice a day, preferably in the early morning and toward evening. When night passes into day and day passes into night, there is a state of relative calmness. At those times, your body will also have a tendency to become calm. Take advantage of these natural conditions and practice then. Make it a rule not to smoke or eat until you have practiced. If you do this, the sheer force of hunger will prevent any tendency to laziness.

If possible, it is best to have a room devoted to your practice of Yoga and to no other purpose. Do not sleep in that room; you must keep it holy. You must not enter the room until you have bathed and are perfectly clean in body and mind. Place flowers and pleasing pictures in the room. Have no quarreling, or anger or unholy thought there. Allow only those persons to enter who are of the same thought as you are. Eventually, an aura of holiness will pervade that space, and when you are sorrowful, doubtful or disturbed, entrance into that room will make you calm. If you cannot afford a room, set aside a corner; if you cannot do that, then find a place inside your house or out where you can be alone and where the prospect is pleasing.

Sit in a straight posture. The first thing to do is to send a current of holy thought to all creation. Mentally repeat, "Let all things be happy; let all things be peaceful; let all things be blissful." Do so to the East, South, North and West. The more you do, the better you will feel. You will find that the easiest way to make yourself healthy is to see that others are healthy, and the easiest way to make yourself happy is to see that others are happy. Afterwards, if you believe in God, pray. Do not pray for money, or health, or heaven, but for knowledge and light; every other prayer is

selfish. The next thing to do is to think of your own body and see that it is strong and healthy. Your body is the best instrument you have. Think of it as being adamant. Like a strong ship, it will help you to cross this ocean of life. Freedom is never reached by the weak. Throw away all weakness. Tell your body it is strong; tell your mind so. Have unbounded faith and hope in yourself. By following the instructions above, you will open your mind to the Yogic forces. Another important aspect of Yoga, the postures, will be discussed in a later section.

The Secret of Prana

Pranayama may seem at first to be totally involved with breathing. However, breathing is only one of the many exercises through which we get to the real pranayama, or control of the prana. According to old Indian philosophers, the universe is composed of two materials, one of which is called akasa, the omnipresent, all-penetrating existence. Everything that has form, or that is made up of compounds, evolves from the akasa. The akasa becomes air, liquids, solids, the sun, moon, stars and comets. It is the akasa that forms animal and plant life. It is everything we see, all that can be sensed and everything that exists. It cannot be perceived, as it is so subtle that it is beyond all human perception. It can be seen only when it has become gross and taken form. At the beginning of creation there was only this akasa, at the end of the cycle, solids, liquids and gases melt into the akasa again, and the next creation evolves from the akasa.

The akasa is manufactured into our universe by the power of prana. Just as akasa is the infinite omnipresent material of our universe, so is prana the infinite, omnipresent

power of this universe. At the beginning and at the end of a cycle everything becomes akasa and all the forces that are in the universe resolve back into the prana. In the next cycle, out of this prana is evolved everything that we call energy or force. It is the prana that is manifested as motion, the power of gravity and magnetism. The prana is manifested as the actions of the body, nerve currents and thought. All thought and all physical motion are manifestations of prana. The sum total of all force in the universe, mental or physical, when resolved back to its original state, is called prana. The knowledge and control of this prana is really what is meant by pranayama.

This opens the door to almost unlimited power. Suppose, for instance, one understood the prana perfectly and could control it. What power on earth could there be that would not be his? Many believe he would be able to move the sun and stars out of their places, to control everything in the universe from the atoms to the biggest suns because he would control the vital force of the universe, the prana. When the Yogi becomes perfect, there might be nothing in nature not under his control. All the forces of nature might obey him as his slaves. But let us not reach beyond the stars!

The control of the prana is the one goal of pranayama. This is the purpose of the training and exercises. Each man must begin where he stands, must learn how to control the things that are nearest to him. Your body is the nearest thing to you, nearer than anything else in the universe, and your mind is the nearest of all. The power which controls this mind and body is the nearest to you of all the prana in the universe. Thus, the little wave of prana which represents your own mental and physical energies is the nearest wave of all that infinite ocean of prana. You must first learn to

control that little wave of prana within you. If you will analyze the many schools of thought in this country, such as faith-healers, spiritualists, Christian Scientists, hypnotists, therapists and many psychologists and psychiatrists, you may find that each attempts to control the prana. Following different paths, they stumbled on the discovery of a force whose nature they do not know, but they unconsciously use the same powers which the Yogi uses and which come from prana.

This prana is the vital force in every being and the finest and highest action of prana is thought. There are several planes of thought. Instinctive thought has been called "conditioned reflex" by Western scholars. If a mosquito bites you, your hand will strike it automatically. All reflex actions belong to this plane of thought. There is also a higher plane of thought, the conscious. You reason, judge, think, see pros and cons of certain situations.

Reason, however, is limited; its sphere is very small. We are constantly confronted with facts which penetrate our consciousness from the outside, facts which are ordinarily beyond the powers of the reason. The Yogi believes the mind can exist on this higher plane, the superconscious. When the mind has attained to that state which is called samadhi—perfect concentration or superconsciousness—it goes beyond the limits of reason, and comes face to face with facts which instinct or reason can never know. Manipulation of the subtle forces of the body, which are different manifestations of prana, if trained, stimulates the mind, which progresses to the plane of the superconscious.

Let us repeat that pranayama has little to do with breathing, except insofar as breathing is an exercise which helps you attain control of the vital forces. The most obvious manifestation

of prana in the human body, therefore, is the motion of the lungs. If that stops, all the other manifestations of force in the body will also stop. This is considered to be the principal gross motion of the body. To reach the more subtle, we must utilize the grosser and so travel toward the most subtle. Breath does not produce the motion of the lungs. On the contrary, the motion of the lungs produces breath. Prana moves the lungs, and the motion of the lungs draws in air.

From the explanation above, it can be seen that pranayama is not breathing, but controlling that muscular power which moves the lungs. Muscular power which travels through the nerves to the muscles and from those to the lungs, making them move in a certain manner, is the prana. Once this prana is controlled, we find that other actions of the prana in the body slowly come under control. If we have control over certain muscles, why not obtain control over every muscle and nerve? What stands in the way? At present, control is lost, and the motion has become automatic. We cannot move our ears at will, but we know that animals can. We do not have that power because we do not exercise it. This is what is called atavism.

We know that physical agility which has been lost can be brought back to manifestation. It has been shown, moreover, that by sincere work and practice, it is not only possible, but even probable that every part of the body can be brought under perfect control.

4. OBTAINING RELAXATION THROUGH YOGA

While the asanas or postures which will be described later are a basic part of the practice of Yoga, we should continue our study of Raja Yoga, the non-physical phases of this practice. Some readers may find they cannot follow the rigid discipline of a full Yogic life; others may be seeking an easier path to relaxation, and may feel that they are less concerned with their physical than their mental states.

Breath control is an essential first step in obtaining a state of relaxation. If you can, assume the Padmasana or Lotus Pose (page 35) or place yourself in a comfortable sitting position. Taken directly from the ancient Sanskrit texts, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika of Swatmaram Swami, published in 1893, provides a specific guide for relaxation through breathing exercises.

There are three Yogic terms which you should know: "puraka" is the term for inhalation; "rechaka" for exhalation; "kumbhaka" for retention of breath. Yogic instructions are: the Yogi assuming the Lotus Pose should draw in the prana (breath) through the ida (left nostril), and, having retained it as long as he can, exhale it through the pingala (right nostril). Again, inhaling through the right nostril, he

should hold his breath as long as possible and exhale slowly through the left nostril. He should inhale through the same nostril by which he exhaled and having restrained the breath to the utmost (until he is covered with perspiration, or until his body shakes) he should then exhale slowly, as exhaling forcefully would diminish the energy of the body.

These exercises should be performed four times a day—in the early morning, at midday, evening and midnight—slowly increasing the number from three, each time, to eighty. Their effects are described as "to render the mind and body slender and bright." Although in the direct translation from the Sanskrit, the ida is named as being the left nostril and the pingala as the right one, these words more properly designate the two supposed conduits which connect with the nostrils, and thence conduct throughout the entire body the vital air (the prana) that enters with the atmospheric air.

Before undertaking these exercises, persons of phlegmatic temperament are directed to go through the following course of preparation: (1) Cleanse the gullet with a strip of cloth, the width of four fingers, by swallowing it and then withdrawing it. Start gradually at the rate of one hand-span's length daily; (2) Take daily enemas of water; (3) Cleanse the nostrils by putting up a thread and drawing it out by way of the mouth; (4) Look without winking at a minute object with concentrated mind until the tears come; (5) With head bent down, turn the viscera of the body to right and left; (6) Breathe in and out rapidly, like a bellows. Internal concentration, causing the stomach to empty itself by vomiting, is also recommended.

According to the Hindu system of physiology, there are seventy-two thousand nadis or channels leading from the throat to the kundali in the pelvic region. When these channels

have been purified by proper breath control, the body is ready to absorb the fullest prana from the atmosphere. Then, according to the old tracts, "the body becomes lean, the speech eloquent, the inner sounds of the individual's body are distinctly heard, the eyes are clear and bright, the body is freed from all disease, the seminal fluid is concentrated, the digestive fire is increased and the nadis are purified."

Looking Inward for Relaxation

It is known that long and close concentration upon any given part of the body will induce sensations there and, sometimes, even movement. Control over unused muscles may be obtained in this way. While it is a basic claim for Hatha Yoga that the breathing exercises can lead to control over the mind by supplying arterialized blood to the brain, and thus control mental by physical action, it is also claimed that strong, persistent concentration of the mind will induce controlled breathing, thus directing physical action by mental.

A story is told of a student whose teacher made him sit meditating in silence for twelve years and at last commanded him to pronounce the sacred syllables A.U.M. This he did with the following results: "When the student came to the first syllable, rechaka, or the process by which the air in the lungs is pumped out, set in naturally. When he finished the second syllable, puraka, or the process of inhalation, set in. At the end of the third syllable, kumbhaka, or the process of retention, set in, and in a short time he had settled into the pure and elevated state of samadhi, which may be defined as perfect relaxation."

This story illustrates the largeness of the claim on behalf of Raja Yoga, or mental Yoga, that it brings physical Yoga with it, provided that the mental processes take the form of long-continued silent concentration. It also supports the claim that what it brings is important, since the pranayama of the student soon brought him into perfect absorption.

The Asanas

Though many asanas, or postures, are unsuited to people who habitually sit in chairs, those who practice Yoga often find themselves falling into these poses almost involuntarily. Many believe that the asanas are natural positions of relaxation into which the body falls when freed from the controls of the conscious mind and from the postures into which they have been trained in our so-called "civilized living." William Flagg, one of the first Westerners to probe the secrets of Yoga, once stated: "A leg has jerked itself upwards and pressed the sole of its foot against the other as high up as seemed possible; this has happened hundreds of times." The posture here imitated is sitting on a foot, and its efficacy is supposed to lie in the pressure upon the nerve centers in the foot, leg and region of the perineum.

Another asana resembling the "plant balance" of modern gymnastics is described thus: "Plant your hands firmly on the ground and support your body on your elbows, pressing against the sides of your loins. Raise your feet in the air stiff and straight on a level with the head." This position was attempted while the practitioner was seated in an easy chair, and failed to be completed only because the back of the chair kept the head from falling to the level of the feet. The legs were lifted from the floor and thrust out stiffly, while the weight of the body was made to rest on the elbows, which were resting on the arms of the chair. This was repeated not

only once, but a great number of times. The elbows were pressed against the sides, forcefully and involuntarily hammering themselves violently and repeatedly against the sides, giving excellent massage to both liver and spleen.

The Shavasana, said to eliminate fatigue and induce calmness of mind, is described as lying on one's back at full length like a corpse. Often, when lying on his side, the practitioner has been turned over on his back as though by a power foreign to him, though apparently using his own muscles. This resulted in a curious sensation, which reproduced on the feet, ankles and seat of the body the compression which is obtainable by sitting on the feet, Eastern fashion. It was as if a foreign body were pressed against the person's sides with a force equal to what would be felt in the postures of Hatha Yoga. Sometimes several of the parts in question were acted upon simultaneously.

Another incident of a similar nature is described by Flagg in the practice of the mudras, or acts for putting the body in good condition. The Nauli Mudra is described: "With the head bent down, one should turn right and left the intestines of the stomach with the slow motion of a small eddy in the river." Something like this interior movement is produced by one process of the Swedish movement-cure. It consists of sitting on a stool, bending the body forward as far as possible and rotating the trunk of the body like the spoke of a horizontal wheel. The head represents the tire and the seat, the hub. It was just this movement that, in the case of two persons observed, was set up as often as kumbhaka, or the suspension of the breath, was practiced, neither of them having an idea of such a result. The Nauli Mudra is considered one of the most important of all Hatha exercises, and the body rotation is one of the most effective of the Swedish exercises.

Concentration

A Yoga technique for concentration is expressed as "looking fixedly at the spot between the eyebrows." Many have reported that while cleansing the mind of thought, the eyeballs would of themselves roll upward as far as they could go, and hold themselves there.

The Shambhavi Mudra provides almost complete relaxation by dividing the conscious concentration. It consists of fixing the mind on some part of the body and the eyes rigidly and unwinkingly on an external object. Often while you are concentrating intently with your eyes closed, they will seem to open almost of themselves and fix on some object within range, always rigidly and without winking.

Another direction for the Yogi says: "Direct the pupils of the eyes toward the light by raising the eyebrows a little upward." Often while trying this, your eyebrows will raise themselves as if to get out of the way of the eyes. In the motions noted here and in others, it seems as though an intelligent power beyond conscious reach takes the Yoga adherent out of his own hands. This power appears to assume control of voluntary and involuntary muscles, working them independently of the person's will, though, it should be noted, never against it.

5. CORRECTIVE POSES OF YOGA

The first section of this book discussed the mental, or psychological, approach to Yoga. As you apply the earlier lessons to mental relaxation, you must also bring your body to a state in which it will support your efforts to attain full contentment, relaxation and ease. Ancient teachers of scientific Yoga realized, as do modern physicians, that proper carriage of the body is essential for mental and physical health. You will note that on the following pages there is very little reference to the Sanskrit philosophy of Yoga, for here we put aside the mind and devote our attention to the body. As you assume these postures, however, keep in mind the eight principles of Raja Yoga. They will help you in dealing with both mind and body as you practice Yoga.

At first, spend only as much time on each exercise as you can without feeling fatigued. As the timbre of your body improves and as your mind takes fuller control of your body, you will find it possible to remain in any pose for longer and longer periods. One of the most prevalent causes of sluggishness and disturbance of the digestive organs is faulty carriage of the body, especially above the waist, involving the spinal

and abdominal muscles. Practically all of us are victims of faulty posture and suffer from enteroptosis, a condition in which the stomach, intestines and very often the kidneys, liver and pelvic organs, are dragged downwards and remain permanently out of their correct anatomical positions.

Medical internists will verify the statement that poor carriage retards circulation of large blood vessels. An habitual slouching position causes the blood of the abdomen to stagnate in the liver, inducing a feeling of despondency and confusion, as well as headache, accompanied by coldness of the hands and feet, chronic fatigue and often constipation. The Yoga Institute in Bombay has traced varied disorders of the digestive and pelvic organs and even functional defects of the heart and lungs directly to poor posture habits. Persons who had been approaching invalidity as a result of posture habits are said to have been cured after a few weeks of training. Persons in normal health have gained markedly, physically and mentally, from a short, but regular, corrective posture program.

The proper pose of the body imparts graceful curves to the female figure and an air of strength to the male. The proper posture, as imparted by Yoga, embodies in beauty the feelings of triumph and self-respect, whatever the age or condition of the practitioner. The common drooped and slouching position is both ugly and unhealthy, and invariably reflects a degenerated mental attitude.

Ancient Yogis were perhaps first to recognize the influence of carriage on health of the mind and body. The prime objective of posture in Yoga is not mystic, mysterious or magic, but the achievement of physical ease and poise. An erect posture is recommended to maintain free spinal circulation during prolonged sitting and concentration.

The First Lesson in Yoga Posture

When beginning the practice of Yoga postures, start with the simple prayer pose in a standing position. Medical investigation shows that many corrective and therapeutic benefits stem from even these first simple poses. It is no longer known whether the ancient Yogins, the founders of Yoga, attached any special mystical significance to these first poses. However, they are excellent poses for prayer and meditation.

Stitha-Prarthanasana, or Prayer Pose

This pose helps to achieve steadiness through gradual control of voluntary muscular movements and offers, through steadiness, the best physical attitude for standing prayer; it permits normal standing posture by coordinating skeletal muscles and it corrects postural defects.

While standing, hold your body as tall as possible without actually rising on your toes. Keep your heels together, placing all your weight upon the balls of your feet. Throw your head and chest up, shoulder blades flat. The abdominal muscles should be deflated at their lower part, but not drawn inward, and fuller just below the ribs, while the pelvis should be tilted at such an angle as to prevent any exaggeration of the lumbar curve. Your knees must be straight but not stiff, with legs together touching at the knees. Fold your hands over the sternum; avoid tension. Relax your mind and fix your eyes on any pleasing object before you.

In this position, the thorax is full and round; the diaphragm is high; the abdomen at its greatest length. The stomach and intestinal viscera are held in proper place and the pelvic organs are relieved of pressures from above. There is a partial relaxation of the larger muscles and relief from

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Stitha-Prarthanasana, or Prayer Pose

tension. With the arms relaxed and let down at the sides, it is an ideal position for standing. Maintain this position for about one minute, breathing normally. Keep your mind free and observe complete silence. Turn slowly to either side, parallel to a wall or post, and notice whether you sway. Swaying is an indication of nervous disturbance which must be overcome.

If possible, practice opposite a mirror, where swaying motions can be noted. During the period of test and correction, keep your eyes half-closed, allowing just enough vision for observation, and concentrate on the parts of your body above the waist. Stand immobile as a statue, and as soon as you have a tendency to sway, check it by will power. After the first few weeks, try to sustain this motionless pose for two to three minutes, always breathing normally. This pose is best practiced in the morning, and should be followed daily until complete control has been achieved. Afterwards, it may be practiced once weekly.

Ekapadasana, or One-Leg Pose

Begin by assuming the Prayer Pose. Bend down, lift one leg with your hands and bring it up to the thigh. Keep your balance on the other leg. If you experience the fear of falling, stand and practice near a wall or window sill or other support. After you have attained sufficient steadiness on one leg, adjust the raised leg by pressing the heel tightly against the opposite groin, with the sole of the foot against the opposite thigh. Study the illustration (page 34) for details of this pose.

Steadiness, or nerve control and coordination between muscular and nervous systems, is one of the prime goals of Yoga physical education, and must be learned in slow stages. At first it may be necessary to use some support to maintain

Click to enlarge

Ekapadasana, or One-Leg Pose

balance. Later you will be able to practice without support, maintaining this pose with your hands in the prayer posture. It may be difficult to keep this pose for more than a few seconds at the beginning, but you should gradually be able to extend the duration of time until you can keep the pose comfortably for two or three minutes. Do not overdo at first. Limit practice to one or two minutes mornings and evenings, alternating legs.

In addition to exercising and relaxing the muscles and nerves of alternate legs, this pose helps to develop the nerve control necessary for relaxation. When swaying is experienced during this exercise, the best corrective is to concentrate your mind on each of your movements. Become consciously aware of the most insignificant variations in steadiness, so that you will be able to secure control over all motion. Along with other Yoga measures—meditation, diet, etc.—this posture facilitates nerve control in the course of a few months.

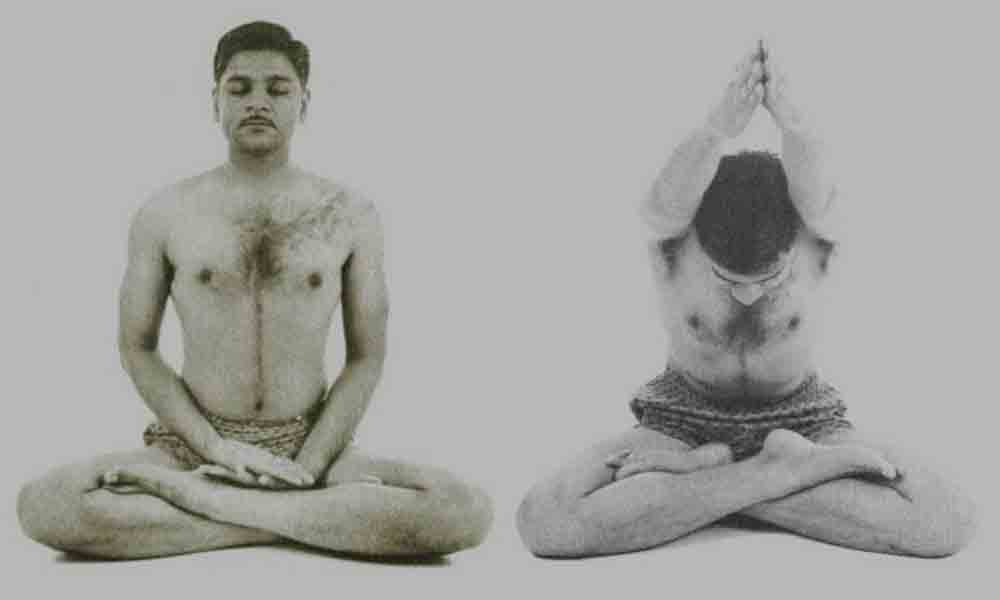

Padmasana, or Lotus Pose

The traditional meditative posture, the Padmasana, or Lotus Pose, is essential for posture training, body-free meditation and preserving normal elasticity of the muscles connected with the pelvis and lower extremities. As noted previously, those who have been raised in the Western culture are stiff and lack flexibility in their legs and lower bodies. This must be corrected in order to restore natural suppleness of the limbs. The Lotus Pose may at first be a bit difficult, but with regular practice, massage of the limbs and determination, it can be achieved. Avoid undue strain and do not force yourself into this by violent jerks or tension of your legs. When you are ready for it, your body will fall naturally into the desired posture.

Now that you have begun the sitting and the lying-down exercises, you should avoid the use of a bare floor. If the room in which you are practicing is not carpeted, provide yourself with a soft mat at least 6 x 3 feet, and spread a clean sheet over the area where you will sit or lie.

Click to enlarge

Padmasana, or Lotus Pose

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Ardha-Padmasana, or Semi-Lotus Pose

Ardha-Padmasana, or Semi-Lotus Pose

Beginning with the Lotus Pose, sit on the floor with your legs stretched out. Bend the right leg slowly and fold it upon itself. Using your hands, place the right heel at the root of the thigh so that its sole is turned upwards and your foot is stretched over the left groin. Similarly, bend the left leg and fold it upon itself with your hands, placing the left heel over the root of the right thigh. Your ankles should cross each other, while your heel-ends touch closely. The left foot with its upturned sole should lie fully stretched over the right groin. Keep your knees pressed to the ground, feet tight against the thighs, and press your heels firmly against the upper front margin of the pubic bone slightly above the sex organs.

To complete this pose, hold your body erect, with neck straight, chest thrown forward and abdomen drawn moderately inwards. Fix your eyes on any object in front of you, then close them. Spread your left hand with its back touching both heels, palm upwards. Place your right hand over the left in the same manner. The ancient texts associate this pose with peace. Although many find it easier to achieve the pose by folding the left leg first, you may alternate the position of your legs.

A highly effective meditative posture, the Semi-Lotus Pose offers many corrective and cultural benefits. It results in either extension, flexion or relaxation to almost all the important muscles, ligaments and tendons of the lower limbs. It also induces increased blood circulation in the abdominal and genital areas by blocking the flow in some areas and drawing a larger supply of blood from the bifurcation of the abdominal aorta. Restraint of the general circulation

caused by the pressure of the heels provides an increased supply of blood to the sex organs and also helps to tone the various nerve centers located in the pelvic region, such as the chain of coccygeal and sacral nerves.

Respiration is improved as a result of the chest being thrown forward and the abdomen being held in normal position. Muscle tone is increased in the internal organs, especially those of the intestinal tract. In this posture, it is important that the shoulders should not sag forward, crowding the chest, nor should the upper part of the body crowd down upon the stomach and the abdominal viscera. The Lotus Pose is suggested for the regulation of breath movements.

Yastikasana, or Stick Pose

This is a recent addition to the traditional asanas, or poses. Developed in the 19th century by Yoga practitioners, it is believed to increase the height of the user. While this benefit may be questioned, the pose induces a state of complete relaxation. An all-body stretch which does not strain even the novice in Yoga, this pose is most easily held while lying down.

To take this pose, harmonize your breathing with your actions. Lie on your back on a comfortable mat or carpet, with your legs and arms fully extended. Fall into a relaxed position. Inhale for three seconds and, while retaining your breath, stretch your body slowly to full length. Your toes and fingers should point outwards, as if trying to reach an object beyond their grasp. Repeat this stretch position for three seconds and then release the tension of the stretch

Click to enlarge

Yastikasana, or Stick Pose

while exhaling. Any maximum stretching of the body should be attempted only while the breath is retained. Do not attempt to hold your breath for more than four or five seconds.

To simplify the explanation of the Yastikasana movements: (1) With body supine, arms and legs outstretched, inhale for three seconds; (2) while your body is outstretched, hold your breath for three seconds; (3) return to the starting position; exhale for three seconds. Repeat the entire exercise five times in one minute.

The primary object of this posture is to stretch the body fully. It serves to correct faulty postural habits and tenses the usually relaxed abdominal and pelvic muscles.

According to the schools of Yoga which have utilized the Stick Pose, stretching aids height and its regular practice will at least halt the tendency of the aging to lose height. It may be done both in the morning and in the evening. Where it is used solely for relaxation, normal, rhythmic breathing should be maintained without any effort at stretching.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Parvatasana, or Mountain Pose

Parvatasana, or Mountain Pose

Overweight can bring both mental and physical problems. The posture known as Parvatasana, or the Mountain Pose, has been found in several Yoga institutes to be highly effective in maintaining slimness and in correcting minor postural defects of the spinal cord.

Assuming the Semi-Lotus Pose, slowly raise your hands upward and above the head. Keep your palms pressed together. If it is easier, interlace your fingers. Finally, stretch upward as if to touch some object directly above your head. Keep your arms close to your ears, your head erect, your back straight, and pull your abdomen in. While inhaling, raise the upper part of your body to its maximum height. Make sure your elbows and wrists are in a straight line.

Maintain this slightly stretched, upright position between breaths, since this is the point at which attempts at upward stretching are most successful. During this exercise, keep your eyes fixed on some object before you and keep your mind at ease. This pose was named Parvatasana because it has the appearance of a mountain.

For maximum benefits, the movements and breathing should be in harmony with actions as shown in the following instructions: (1) In a sitting pose, raise arms and inhale for three seconds; (2) maintain pose and try to retain breath for six seconds; (3) return to starting position, exhale for three seconds. Repeat this pose five times to a minute without pausing.

This posture tenses and pulls all the abdominal and pelvic muscles, strengthens and straightens the muscles of the back and also stretches and exercises the usually inactive waist zone. One of its most evident benefits will be the reduction of fat and flabby abdominal tissue. However, it must be followed consistently for one minute, both in the morning and evening.

Variations of the Parvatasana Pose

There are four dynamic variations of this pose. They are: (1) Swaying forward; (2) leaning backward; (3) bending to the right; (4) bending to the left. These variations should be utilized during a six-second breathing pause. Instead of maintaining the perpendicular position while stretching, vary it by making the movements on the four sides and alternately. Gradually increase the retention of your breath to nine seconds, which will permit four movements to a minute. The purpose of the variations is to provide additional

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Variations of the Parvatasana Pose: forward,

backward, right and left.

stretching of all sets of muscles in the trunk. They also massage the internal organs just below the ribs and the abdominal muscles.

Trikonasana, or Triangle Pose

The Trikonasana will enable you to reach a state of physical suppleness and elasticity that will have a relaxing effect on your mental state. It is more difficult at first than the earlier poses, as it calls upon ordinarily unexercised muscles. Because of the exceptionally straight and full-length adjustments of the bony structure of the spine, this pose will correct many of the ailments due to misplaced internal organs and poor body tonicity. The dynamic variations of this pose will enhance its benefits considerably.

Stand erect with your feet together and arms down at your sides. Slowly exhale while bending downward; keep your legs straight. Lower only the upper part of the body. Keep your legs perfectly straight and pressed backwards. Now, touch your toes with the tips of your fingers, keeping your arms straight, with spine and neck horizontal, abdomen in, head thrown forward, and your eyes fixed on the tip of your nose. Maintain this pose as illustrated on the next page, then return to the original position while inhaling. Your movements and timing should be as follows: (1) Touch toes and exhale for three seconds; (2) keep pose and hold breath for six seconds; (3) return to starting position and inhale for three seconds. Repeat five times in one minute without pausing.

Do not become discouraged if you fail to touch your toes on the first attempt. Try each day until you can hold the pose comfortably. Work into this pose gradually, avoiding attempts to force your body into it by jerks or sudden

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Trikonasana, or Triangle Pose

pulling of muscles. Before working for other refinements of the pose, aim to touch your toes. If you should find yourself feeling muscle tenderness, try a warm massage to alleviate the discomfort.

A dynamic variation of the Triangle Pose is fairly simple. Stand with your feet twenty-four inches apart and, while inhaling, raise one arm and bend it laterally on the opposite

side, sliding the other arm lengthwise. When the complete lateral stretch is achieved, retain your breath and return to the original position. Repeat the lateral stretch on the other side.

Movements, breathing and timing should be as follows: (1) Bend sideward; inhale for three seconds; (2) keep pose and retain breath for six seconds; (3) return to normal position and exhale for three seconds. Repeat alternately, without pausing, ten times in two minutes.

For best effects, the exercise should be practiced for at least one minute. However, persons with poor physical tone and those with a history of circulatory or respiratory ailments should try it only in moderation, for about ten seconds at one time.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Variations of the Triangle Pose

Garudasana, or Eagle Pose

Another cause of both physical and mental tenseness is a lack of suppleness and elasticity in joints and extremities. Correctives for this are postures involving fairly simple body twists. The purposeful twisting of the extremities may be accomplished through the Garudasana.

Click to enlarge

Garudasana, or Eagle Pose

Stand erect as shown in the illustration. Lift either leg (the alternate use of each leg will follow), and twist the same leg both near the hip joint and the knee. Then twine one leg around the other. Adjust the twists very carefully without strain or muscle tension. Lock the ankle with the toe of the other twisted leg and hold it there as a safety against possible accidental release. Do this while exhaling. When you are balanced on one leg, make an effort to keep the body straight, and gradually increase the pressure of the toe-hold near the opposite ankle until the greatest possible twist is achieved.

At first, practice only the leg twist while retaining your breath. After the first week or so, when this becomes easier, try the arm and hand twists by twining one arm around the other (alternating arms). Twist the hands from the wrists and press the palms against each other. Try to keep

the pose for several seconds and, while inhaling, return to the original position.

Do not force yourself into this pose until your limbs have gained sufficient suppleness. Then you should follow this time-plan: (1) Twist your body and exhale for five seconds; (2) maintain the pose as shown in the illustration and retain your breath for ten seconds (or you may with normal, rhythmic breathing hold the pose for not more than two minutes); (3) return to starting position and inhale for five seconds.

It is advised that this posture be repeated alternately three times on each side for a two-minute period, preferably in the morning. Note that in the Garudasana you should avoid straining while twisting. Practice it by gradual stages before attempting to follow the full exercise.

6. SPECIFIC ASANAS FOR WEIGHT REDUCTION

The slim, svelte figure is a goal of our culture, especially for the female sex, so that the next series of asanas may be of particular interest to women. From the point of view of Hatha Yoga, the elimination of excess fat has been one means of achieving body-mind harmony. Even before modern insurance actuaries pointed out the correlation between excess weight and high mortality, Yogis had determined that every pound of weight above normal (particularly for persons over forty) shortens life by one year. While many persons have ruined their health and even courted death by attempts to lose weight through chemical pills or starvation diets, the Yoga reducing method improves body tone while it trims excess poundage. One of the goals of Hatha Yoga is mrnalakomalavapu, or the slimness of a lotus stalk.

Recent medical findings on overweight, which were also foreshadowed by the Yogins, indicate that the accumulation of body fat is a symptom rather than a disease. In the great majority of cases, obesity is due to psychological rather than physical causes. In a small number of persons, obesity may result from faulty or subnormal functioning of the endocrine

glands. However, most fat people owe their condition to overnutrition or underoxidation of the food consumed, or a combination of both. Unused surpluses of ingested food are deposited in the body tissues as fat, and accumulate in those parts of the body which are least affected by muscular action. Fatty deposits in certain parts of the body may not be too noticeable, but deposits in the area of the hips and abdomen are both unsightly and difficult to remove by ordinary means. Everyone has heard the complaint of the dieter that "my face looks thinner, but the fat stays on my hips and stomach!"

Another aspect of obesity which is generally overlooked by the reducing faddist and the Western exercise "schools" is that improper elimination is a great contributor to stoutness. One of the basic objectives of the Yoga postures in the reducing regime is to exercise the trunk and mid-trunk. At Yoga institutes in India it has been found that the first successful step in the removal of excess fat is to combat constipation by eliminating the use of laxatives and substituting proper Yoga exercises. These postures and movements, which massage internally and invigorate the muscles and walls of the abdomen, have been found to be successful in the treatment of cases of functional and chronic constipation.

While the Yoga postures discussed above enhance tonicity of the extremities, hygiene of the trunk is important for general good health and is especially important for tense or obese persons. The daily postural exercises already described will supply adequate tonicity to the thorax. However, special attention is needed for the abdomen and the waist. Abdominal tonicity can be achieved in two ways: by systematic exercise of abdominal muscles by anterior and posterior movements, and through mechanical effects on the inner muscles by intra-abdominal compression.

Hastapadangustasana, or Toe-Finger Pose

The Toe-Finger Pose offers a variation for forward and sideward movements. Stand erect with your legs straight, chest thrown forward and hands at your sides. While exhaling, slowly raise one leg straight forward, until it is at a right angle to your body. Avoid bending your knee. Balancing your body on one leg, stretch your arms forward, and either touch or take hold of the raised leg with the fingers of one or both hands. Maintain this position for only a few seconds at first, during suspension of breath. Inhale while returning to the starting position.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

With practice, you'll be able to straighten

your leg completely in the Toe-Finger Pose.

Repeat this posture three times in one minute, lifting each leg alternately. For best effects, do it in the morning. To establish harmony between motion and breathing: (1) Raise leg forward and exhale for two seconds; (2) maintain pose as shown in illustration and exhale for four seconds; (3) return to starting position and inhale for two seconds.

A variation of this pose is to raise your leg sideways instead of forward. Other movements remain unchanged. If you are unaccustomed to exercise, start by lifting your leg without attempting to touch or hold your toes.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Hastapadangustasana, or Toe-Finger Pose

You will probably find that in the early stages your fingers cannot be made to touch your toes, or that your knee tends to bend. Try to rectify these errors each time you practice the posture. If, however, you feel muscular strain, place your hands on your hips and practice the leg movements with the appropriate breathing. An analysis of the benefits of this pose shows that the flexion of the hip, followed by exhalation, increases abdominal compression. In addition, slow, steady, alternate movements provide a mild internal massage to the viscera by utilizing the muscles and tendons of the normally inactive lower abdomen and hips.

Hastapadasana, or Hand-Leg Pose

Consistent practice of the Toe-Finger Pose should improve the flexion of your hips. As this proceeds, you should also try to increase the intra-abdominal pressure through an exercise which induces maximum stretch of the posterior muscles. This may be achieved by utilizing the Yoga Hand-Leg Pose, or Hastapadasana, and its variations.

Start this pose with the now-familiar Triangle Pose, standing erect with your feet together. Next bend forward at a right angle, while reaching your toes. Try to keep your feet together and your knees straight. To obtain the hygienic benefits of this posture, it is essential to keep your legs straight.

With your legs straight, exhale and bend forward from the waist slowly. The aim is to be able to hold your ankles with your hands, keeping your head pointed downward. Maintain this position for a few seconds, while suspending your breath. Then return to the starting position, while exhaling. (1) Bend forward, reaching the toes, and exhale for

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Hastapadasana, or Hand-Leg Pose

two seconds; (2) maintain pose for four seconds, while suspending your breath; (3) return to starting position and inhale for two seconds. Repeat the exercise with a two-second pause after each movement. Complete four rounds in one minute.

Grasping your ankles will be difficult in the beginning, but with regular practice it will become easier. When you can comfortably hold your ankles tightly, try to fold your arms near the elbows. Then draw your head closer to your knees. This practice should be continued for several weeks. Finally, try to rest your forehead between your thighs just above your knees. Try this pose with slow, normal breathing at first, especially if you plan to hold it for more than four

seconds. As a precaution, do not breathe in deeply during this pose, for there is a possibility that this could injure the delicate internal organs which are now in a condition of intra-abdominal pressure.

This is probably the first really difficult posture that you have attempted. For the best results, allow a fairly long time for the completion of the posture. Keep in mind that the goal is not to become proficient at holding the pose, but to acquire the benefits of regular practice. Undue effort that causes muscular strain or a feeling of personal inadequacy will be harmful. A posture which cannot be achieved in the morning may often be attained in the evening, since the day-long use of the body may make the limbs and trunk more supple. Women should not practice this posture or any other which involves intra-abdominal pressure during the first three days of menstruation or during pregnancy.

Purpose of These Poses

The benefits derived from the poses just discussed result from their twofold action. They effectively stretch the posterior muscles which support the abdomen, hips and waist, thus increasing the tone of the abdominal and pelvic organs. They also help to loosen and reduce unhealthy and unnecessary fatty tissue. Above all, they effectively reduce constipation and induce natural, regular elimination. Much tenseness and stress is not due to the pressures of outside influences or nerves, but results from bodily discomfort because natural functions are hampered. The noxious effect of autointoxication is caused by a lack of proper tonicity. This is what the Yoga postures and exercises can overcome if followed faithfully—the achievement of "mens sana in corpore sano"—a sound mind in a sound body.

7. SPECIFIC POSTURES FOR RELAXATION

While the great majority of the asanas have a curative or therapeutic value, there are several which are purely for the purpose of relaxation. Relaxation should not be mistaken for inertia. It is not a state of lethargy; rather, it is rest after effort or, perhaps, conscious rest after conscious effort. One definition of relaxation is "a complete resignation of the body to the power of gravity, surrender of the mind to nature, and the whole body energy being transferred to a deep, dynamic breathing."

Physical Relaxation

Complete relaxation of the voluntary muscles at once transfers energy to involuntary parts so that, strictly speaking, there can be no such thing as relaxation except in the voluntary muscles and brain. But this is quite sufficient! This transfer of energy by voluntary action and involuntary reaction produces the necessary equilibrium for the renewal of strength.

In many parts of the world, where human beings still

transport heavy loads, it is amazing how far they can carry burdens that most individuals could not even lift from the ground. Observation of porters in many parts of the Orient and the Arabic world has shown that their endurance may be due to the ability to relax. During long, heavy hauls, they often stop and lie down in apparently semi-lifeless states for as long as an hour. Then they rise, refreshed, and resume their arduous journeys.

Proper, purposeful relaxation offers the greatest amount of renewed strength in the shortest length of time. After extended exertion or stress, perfect rest in the form of relaxation is the principle which revitalizes the nerve centers, collects the scattered forces of energy and invigorates the body. The three poses of Yoga for complete relaxation are Dradhasana, Shavasana and Adhvasana.

Dradhasana, or Firm Pose

This is considered best for sleeping, as it is the most comfortable. To take the pose, lie relaxed with your right arm under your head, using it as a pillow. By lying passively on the right side, you favor emptying of the stomach and make breathing movements easier. In practice, it has been found that sleeping in this manner generally inhibits dreams

Click to enlarge

Dradhasana, or Firm Pose

and nocturnal emissions and improves digestion. A short period of sleep becomes the equivalent of a longer sleep for recuperative purposes. It is also recommended for short periods of waking relaxation.

Shavasana, or Corpse Pose

This is recommended for use when the student of Yoga experiences fatigue during any of his exercises. This pose is described in the tracts as "destroying fatigue of the body; quieting the agitation of the mind." Lie face up with your feet extended. Remain motionless with a sense or feeling of sinking down like a corpse. Gradually relax every muscle of the body by concentrating on each individually, from the tip of the toe to the end of the skull. Exercise absolute resignation of will by trying to forget the existence of your body and detaching yourself from it. Hold this posture until you feel restored.

Medical authorities have confirmed that the Shavasana pose brings about a fall in the blood pressure and pulse rate and establishes an even rate of respiration. If this pose is kept for more than ten minutes, the deepened respiration and lowered circulation in the brain will probably bring about a tendency to sleep.

Click to enlarge

Shavasana, or Corpse Pose

Adhavasana, or Relaxed Pose

Lie down with your head on your folded arms, as if on a pillow, and concentrate as in Shavasana. Relax all your muscles. Then stretch your hands and legs out fully, and permit the power of gravity to take over the weight of your body as you relax every voluntary muscle.

Click to enlarge

Adhavasana, or Relaxed Pose

Mental Relaxation

Another group of asanas, or postures, specifically provides for the care of the nervous system. These exercises have been found to be especially helpful to persons of a neurasthenic condition. An individual in this state will be mentally vague, lack determination, and have continual feelings of inferiority, fatigue and distraction, accompanied by a state of anxiety. Lack of will power and other forms of nervous or mental debility are all indications of a lack of tonicity in the brain-nervous system.

In many ways, symptoms of the neurasthenic are similar to those of an older person who is approaching or has reached senility. Yoga investigators feel that the condition may be

due to a degeneration of the nerve cells with resultant subnormal functions. While the Yoga process may not reverse the situation in the case of an aged person, it has resulted in relief for neurasthenics of young and middle age. In addition, the normal person who utilizes these asanas will find that he derives from them a new keenness of mind and an ability to utilize his nerve-energy to the utmost for whatever personal goals he may have set for himself.

Bhujangasana, or Snake Pose

The anterior and posterior stretching offered by the Snake Pose are said to be ideal spinal exercises, preserving or restoring tonicity in the spinal column and nervous channels. Lie on your stomach, with your legs stretched and toes pointed outward. Keep your arms at your sides, with palms down, and your forehead on the floor. Then, slowly raise your head and neck upward and backward.

When your head and neck are slightly raised, plant your hands on both sides of the abdomen. Inhale, and gradually raise your thorax and the upper part of your abdomen by increasing the angle between your hands and rising shoulders. From the navel downward, your body should remain fixed to the ground. Only the upper portion of your body should be raised. In some texts, this pose is called the "Like a hooded cobra striking" pose. Work toward this pose gradually, avoiding muscular strain or "jerkiness" in your efforts to raise the upper part of your body. As you practice this pose, you will feel the pressure on your spinal column gradually working down the vertebrae until you feel a deep pressure at the coccyx.

At first, concentrate on the posture. Having achieved the

Click to enlarge

Bhujangasana, or Snake Pose

correct pose, exhale and return to the starting position. Lower yourself slowly. In contrast to the pressure which you felt as you entered this posture, you will experience a feeling of relief along your spine as you lower yourself. This asana should not be utilized by women during menstruation or advanced pregnancy, or by men suffering from hernia. Persons with a weak physical structure should approach this asana slowly and drop it if they find it too arduous. It may be attempted later when the other muscle-tone asanas have shown their effects.

After the pose has been mastered, follow this procedure: (1) Raise thorax and inhale for three seconds; (2) maintain pose, retaining your breath for six seconds; (3) return to starting position, while exhaling for three seconds; (4) repeat five times in a minute.

It is suggested that the Snake Pose be practiced for at least a month, by which time its effects should be felt. Practice it daily, preferably in the evening before dinner.

Halasana, or Plough Pose

The Snake Pose is actually the first of a linked pair of postures, the second being the Halasana, or Plough Pose. This pose should be undertaken when you are fully rested. To start, lie on the floor with your face upward and arms resting at your sides, palms downward. Then raise your legs together, slowly inhaling until your legs are brought at a right angle to the body. Next, while exhaling slowly, raise your hips and lower your legs beyond your head. Keep your legs together and straight. As you become practiced in this posture, stretch your toes further and further beyond your head. If you find this posture too difficult, keep your legs folded or bent and raise them as high as you can. Practice in the following manner: (1) Raise legs to a right angle with body and inhale for two seconds; (2) lower legs beyond head and exhale for two seconds; (3) maintain pose for four seconds while suspending breath; (4) return to starting position, while inhaling slowly for two seconds.

Do not overdo this posture. At first try it once daily, then, as it becomes easier, work toward the completion of six rounds in a minute. It may be easier at first in the evening, when the body is more supple. When perfected, it should be practiced in the morning on an empty stomach. Those who are extremely overweight may find this pose impossible, as will those with stiff muscles. Also, it is not recommended for those with any form of hernia. In addition to its cerebro-nervous system therapy, this pose is highly effective in ridding the body and nervous systems of toxic accumulations and its perfection and regular use will aid largely in achieving purification of the nervous-energy channels.

Click to enlarge

Halasana, or Plough Pose

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

A variation of the Plough Pose, with arms

under head.

Ultrasana, or Camel Pose

This is the climactic pose of the series suggested for nerve-spinal adjustment. Generally it is impossible to achieve before the two previous poses have been perfected. Kneel and while supporting your body on your toes gradually lean backward, after fixing your arms behind you, with your palms to the ground, fingers pointed outward and thumbs toward your toes. Keeping your arms straight, slowly lift your hips while inhaling. Then, push your body above the waist slowly outward and upward, throwing your neck downward. As you come into this posture, you should feel the pressure traveling upward toward your shoulders and neck,

Click to enlarge

Ultrasana, or Camel Pose

finally reaching your neck and facial muscles. It is suggested that this pose be practiced in the morning, but not more than once daily. In timing, the body-lift should take three seconds with inhalation; retention, six seconds; return to kneeling position while exhaling, three seconds.

TIME SCHEDULE FOR PRACTICING THE ASANAS

The time schedule has been established to enable the person of ordinary muscular development to follow a routine of Yogic exercises. After reading the text and gradually taking the step-by-step procedure for the postures and exercises, you should make a copy of this chart and place it on the wall of the room in which you practice the asanas. Do not overdo, as the Yoga exercises are designed for a gradual program of improvement. This is not an easy, one-day course.