Devotion and Meditation in Hinduism

Devotion and meditation are the two fundamental approaches in Hinduism to attain God. In their simplest form, in meditation a worshipper meditates upon God inwardly, while in devotion he worships outwardly by focusing his mind upon an image or a form of God. However, it is possible to combine both practices and worship God meditatively with devotion.

Historically, it is believed that with the rise of Upanishadic philosophy and the advanced rituals of the Forest Books (Aranyakas), the Vedic sacrificial worship, which was originally meant to propitiate the gods, became internalized and developed into the yogic practice of concentration (dharana), meditation (dhyana) and concentrated, self-absorbed meditation (samyama) in which the mind and body became the sacrificial pit and thoughts the offerings and oblations.

Distinction between devotion and meditation

In Hinduism, meditation and devotion are both used to practice divine worship with the same ultimate aim, which is liberation from the cycle of births and deaths. In regular practice it is not uncommon for a Hindu to practice both the methods to purify his mind and body and reach the transcendental state of self-absorption or oneness with the inner Self. In Both cases, the object of worship is either the Supreme Self or the inner Self or both, while the seeker is the subject. Meditation and devotion are the means which lead the seeker on an inward journey of extraordinary adventure to discover himself, his essential divine nature or his oneness with the deity that he worships or meditates upon.

In spiritual practice, both meditation and devotion have their own importance. Some people are drawn to devotion easily, while some are drawn to meditation. Devotion is an intensely physical and mental effort, in which the heart becomes the support whereas meditation is mostly a mental and spiritual effort in which the mind plays a key role. Devotion has a ritual component consisting of certain physical and mechanical functions(charya and kriya) which are meant to ground the devotee's heart in divine love. In meditation also there is a ritual component that involves certain mechanical and physical functions, as part of the spiritual preparation to stabilize the mind in the object of meditation.

There is yet another distinction between the two. In devotional worship, you use your senses and emotions freely to elevate your consciousness to enter ecstatic devotional states. In contrast, in meditation, you withdraw your senses inwardly and try to calm your emotions to enter the supreme transcendental states of tranquility, stability and sameness. Whichever method you may choose, in the advanced stages of both practices, you will enter the same ecstatic state of non-duality (samadhi) and achieve union with your divine nature. According to some scholars like Sri Ramanuja, devotion is a more advanced practice than meditation, which can be practiced in its highest and purest form only after years of effort and achieving perfection in karma and jnana yogas.

Three approaches to meditation and devotion

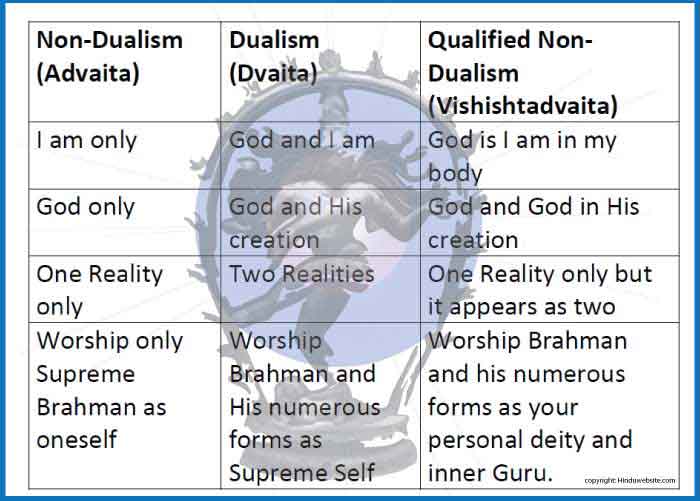

Traditionally, there are three basic approaches in Hinduism for the practice of meditation and devotion. They are based upon the beliefs and practices that are found in the three major philosophical schools of Hinduism, namely non-dualism (advaita), dualism (dvaita) and qualified non-dualism (vishistadvaita). Each has a long history and a long list of distinguished teachers, teacher traditions and temple practices. The fissures they create within Hinduism are deep and lasting, as the debate about their merits and demerits remains unsettled even after 2000 years and continues even today among scholars

The non-dualistic approach

In non-dualistic approach (advaita), which is very difficult to practice, an aspirant worships the Supreme Self only and none else. He acknowledges no deity other than Supreme Brahman and tries to merge his own identity into His by overcoming the duality he perceives between him and his object of meditation or worship. For a non-dualist, Brahman is the one and only reality. Brahman alone is true. Everything else, including his own individuality, is a delusion or a mere appearance, like an outward extension of the Sun in the sky as sunrays. With that understanding, he dutifully ignores or negates all diversity using the famous "not-this, not-this (neti, neti) method," and tries to focus his mind solely upon Brahman to erase all notions of the duality between the knower and the known or between God and him.

Technically a non-dualistic person is not expected to worship any idols, or any physical or mental form of God but only the non-differentiated, formless, universal Brahman (Nirguna Brahman), or simply Brahman as Supreme Consciousness. Whether he practices meditation or ritual worship, for him Brahman alone remains his object of concentration or devotion. Obviously the non-dualistic meditation and devotion are very difficult to practice because it is not easy to stabilize one's mind in a formless, indistinguishable entity that cannot be objectified.

The Bhagavadgita concurs with this opinion. The difficulty arises because the human mind cannot easily transcend duality and comprehend the immutable, indivisible, and indistinguishable nature of Supreme Reality. As the mind is repeatedly drawn into the opposites of our phenomenal existence, it will not settle easily or facilitate tranquility, sameness and oneness. However, although non-dualistic approach is the most difficult, since it is a direct method, those who excel in it achieve liberation quickly.

The dualistic approach

In the dualistic approach, you accept the duality, or the distinction between you and the Supreme Self. Although you acknowledge your inner Self, and your spiritual nature as having some affinity with the Divine Himself, you do not consider them the same but separate and distinct. A dualist perceives duality, or the pairs of opposites, in every aspect of creation, from the highest to the lowest, in his own mind and body and in the entire creation. Since for a dualist, duality is the fundamental, and perceptible reality of the whole existence, he does not try to transcend the duality between him and God, but uses it to practice his meditation and devotion. In both practices, a dualist may temporarily become absorbed in the supreme consciousness and experience union with the Supreme Self.

However, even after he enters the transcendental state, he remains distinctly aware of the separation or the duality that exists between him and his Deity. For his practice of meditation or devotion, a dualist chooses finite forms of God or His numerous aspects, with a clear understanding that the Supreme Infinite and indivisible One manifests in numerous forms to create and uphold numerous worlds and realities. He may worship God as Shiva, Vishnu, Brahma, Shakti, Virata Purusha, or any of the multitude of gods and goddesses who adorn the Hindu universe.

A dualist does not believe that the numerous forms of Brahman are his delusion or mental creations, but real and direct emanations of the same Supreme Self. They are as real to him as he is to himself. In other words, for a dualist everything in the universe is real, worthy of worship, and representative of the same Supreme Being. Thus, while a non-dualist strives to worship or meditate upon the Supreme Being beyond all duality and diversity, a dualist tries to find Him in the diversity itself. For him, the Persona of God is distinct from the Person of God. The persona is His body, the sum of all materiality, corporeality, and diversity, while God Himself is the Supreme Soul. All the beings in the entire existence are persons (purushas), while God Himself is the highest and the most excellent of them (Purushottama).

The qualified non-dualistic approach

The third approach is neither dualistic nor non-dualistic but an intermediary type having the aspects of both philosophies. Hence, it is called qualified non-dualism (vishishtadvaita). In this approach, a worshipper or a meditator accepts God as the only reality, as in case of non-dualism. However, unlike in non-dualism, he accepts God having some personal qualities or attributes such as names, forms, feelings, thoughts, and emotions. Therefore, he believes that if you worship God as your personal deity, or meditate upon Him with a stable mind, He reciprocates with abundant love and grants you liberation. In this neither the devotee nor God (in the opinion of devotee) perceive any duality or distinction between them. They are like a person and his reflection in a mirror. Their hearts are united and so are their pure consciousness. The duality between them arises as they become reflected in each other's nature (prakriti), God in His devotee and devotee in God.

According to the school, God represents the best and the highest. He is made up of supremely pure matter (suddha sattva), while His devotees represent the triple gunas according to their perfection and past deeds. The beings are subject to impurities, delusion and desires, which make them vulnerable to death and rebirth. Although the beings differ in their nature and temperament, and act according to their natural modes (gunas), yet just as the rays of the sun fall on everyone equally with the same radiation and intensity, the love of God is extended to everyone equally with the same intensity. In His supreme wisdom, God does not discriminate between individual souls, but responds readily to the love of his devotees. While we perceive duality in the world and deal with the worldly phenomena with dualistic awareness, God remains in His transcendental supreme state beyond duality and sees no such distinction between Him and His creation.

He treats sinners and saints alike. In saintly people, He becomes reflected in their pure (sattva) nature. In rajasic people, who are worldly and materialistic, He becomes reflected in their rajas quality. In tamasic people, who are by nature deluded and gross, He becomes reflected in their darker tamas quality. As His reflection, so become His devotees. Driven by their gunas, tamasic people worship or meditate upon God in tamasic forms; rajasic people worship or meditate upon God in rajasic forms; and sattvic people worship Him in sattvic forms. In his infinite love, God makes Himself know to everyone according to their degree of purity (sattva) and their essential nature.

A brief overview of the three approaches is summed up in the following table.

The concept of God in Hinduism is uniquely supreme and very advanced

Thus, as you can see, unlike in simplistic and dogmatic religions, in Hinduism God is envisioned and worshipped by devotees in numerous forms and ways. While there seems to be a dichotomy between philosophy and devotional worship, in reality both complement each other. A meditator looks within Himself upon the same reality which a worshipper perceives in an object of worship. In both cases the same approaches are used by aspirants according to their degree of purity, knowledge and understanding.

The different approaches which we have discussed above do not support the flimsy and rather mischievous argument of a few Christian missionaries who want to create an impression that Hindus borrowed the concept of God from Christianity in the early Christian era. The Hindu idea or ideal of God does not arise from the ignorance of the people who practice them or their fear of the unknown. It is not formed from the leftover beliefs of primitive barbaric cultures of the ancient world, but as a direct result of a unique spiritual evolution that happened in the Indian subcontinent, against the backdrop of a long history of ascetic traditions, and several schools of religious philosophy.

The vision of God of such immensity, complexity, diversity and depth found in Hinduism is not evident in any other religion. For millenniums Hindu seers, saints, scholars and spiritual masters physically, mentally and spiritually envisioned and worshipped God in numerous forms and opened as many doors as possible for the aspirants to attain a glimpse of His immeasurable existence. Their collective effort culminated in the validation of the three approaches of present-day Hinduism that can empirically lead any practitioner into an inner journey of profound spiritual experience and heightened awareness.

The devotional and meditative practices of Hinduism are therefore valid and verifiable methods. They conclusively prove that God mellows and manifests in our vision and awareness according to the love and devotion we show and according to the faith we hold in our hearts. They prove beyond doubt that it is possible to connect and communicate with the Supreme Self through ritual and spiritual methods and spiritualize our very consciousness deep into the core of our being. They also confirm and validate the truth that God is not a vengeful and wrathful controller, but a loving and compassionate nourisher and facilitator who manifests in you as your own reflection according to your beliefs, desires, and essential nature. While scholars may debate the efficacy of each of the approaches, the aspirants who follow them with conviction and resolve find them effective in opening their minds to the vision of God and their deeper connection with God Himself.

Suggestions for Further Reading

- Om, Aum, Pranava or Nada in Mantra and Yoga Traditions

- Brahmacharya or Celibacy in Hinduism

- Atheism and Materialism in Ancient India

- Solving the Hindu Caste System

- How To Choose Your Spiritual Guru?

- Creation in Hinduism As a Transformative Evolutionary Process

- Wealth and Duty in Hinduism

- Do You Have Any Plans For Your Rebirth or Reincarnation?

- Understanding Death and Impermanence

- Lessons from the Dance of Kali, the Mother Nature

- Letting your God live in You - The True Essence of the Hindu Way of Life

- prajnanam brahma - Brahman is Intelligence

- Maslow's Hierarchy Of Needs From The Perspective Of Hinduism

- The Defintion and Concept of Maya in Hinduism

- The Meaning of Nirvana

- Self-knowledge, Difficulties in Knowing Yourself

- Hinduism - Sex and Gurus

- The Construction of Hinduism

- The Meaning and Significance of Heart in Hinduism

- The Origin and Significance of the Epic Mahabharata

- The True Meaning of Prakriti in Hinduism

- Three Myths about Hinduism

- What is Your Notion of God?

- Why Hinduism is a Preferred Choice for Educated Hindus

- Essays On Dharma

- Esoteric Mystic Hinduism

- Introduction to Hinduism

- Hindu Way of Life

- Essays On Karma

- Hindu Rites and Rituals

- The Origin of The Sanskrit Language

- Symbolism in Hinduism

- Essays on The Upanishads

- Concepts of Hinduism

- Essays on Atman

- Hindu Festivals

- Spiritual Practice

- Right Living

- Yoga of Sorrow

- Happiness

- Mental Health

- Concepts of Buddhism

- General Essays