The 24 Tattvas of Creation in Samkhya Darshana

Summary: This essay explains the significance of tattvas or finite realities of Nature (Prakriti) according to the Samkhya school of Hinduism.

Hinduism owes a great deal to the Samkhya (Sankhya) philosophy or the Samkhya Darshana. Samkhya means number. The Samkhya philosophy deals with the number of realities that are present in existence. According to Richard Garbe, it is "the most significant system of philosophy that India has produced." It exerted a profound influence on many scholars in ancient India, China, and, according to some, even in Greece. Even today, it attracts the attention of many scholars, although it is not a living philosophy and has no active followers. However, aspects of its original doctrine survive in present-day Hinduism as a reminder of its ancient glory.

We find references to the school in scriptures like the Bhagavadgita, the Mahabharata, and the Upanishads, such as the Svetasvatara and the Maitrayani Upanishads. Although, originally, it might have begun as a theistic philosophy with its roots in the Upanishads, it appears that subsequently, it morphed into an atheistic school that assigned no role to God in creation and attributed all causes and effects to Nature. Its main tenets and ideas gradually found their way into mainstream Hinduism and several sects of Buddhism.

According to the Samkhya philosophy, Prakriti or Nature is responsible for all manifestation and diversity, while the individual souls (Purushas), which are eternal, remain passive. When they come into contact with Nature, they become subject to its influence and are embodied by its realities. Prakriti is an eternal reality and the first cause of the universe. In its pure and original form, it is the unmanifest (avyaktam), a primal resource, the sum of the universal energy. It is without cause but acts as the cause and source of all effects and "the ultimate basis of the empirical universe.”

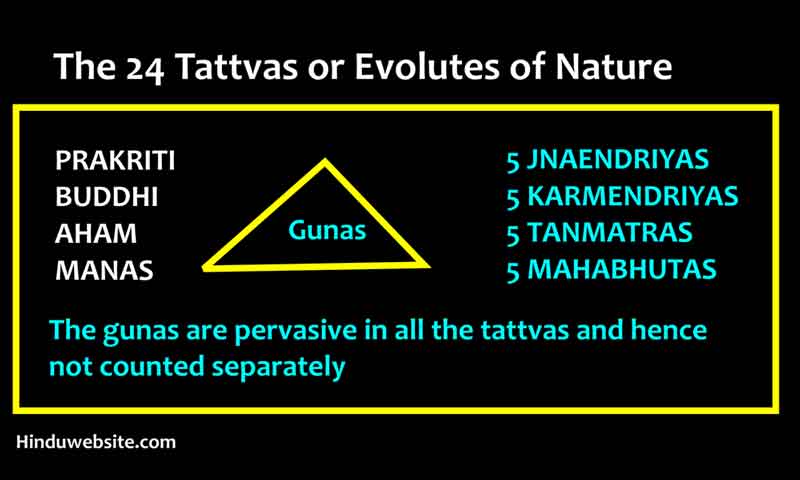

The tattvas or realities

Prakriti manifests things by modifying or transforming the causes into effects that are already hidden in them. Thus, the school believes in the theory of evolution or transformation (parinama vada), with Prakriti acting as the pre-programmed supreme intelligence (Mahat). Using the triple gunas and its various realities (tattvas), it creates the diversity of numerous beings and objects. However, Prakriti has no power or control over the souls (Purushas), which are eternal, numerous, independent, and immutable. It cannot also create life forms without the participation of the souls. Creation (Shristi) begins when the equilibrium of the gunas (modes) in Prakriti becomes disturbed, and its realities (tattvas) manifest as organs in the beings (jivas). According to the school, all 24 realities (tattvas) emerge or evolve out of Nature, each having the predominance of one or more gunas. The 24 tattvas are listed below.

- Prakriti, the Primal Nature (1)

- Mahat, the Great One, The first evolute of Prakriti (2)

- Buddhi, discriminating, reasoning, and causative intelligence (2)

- Ahamkara, ego or ego-principle (3)

- Manas, the physical mind or brain (4)

- The five panchendriyas, sense organs (9)

- The five karmendriyas, the organs of action (14)

- The five tanmatras, subtle elements or sense perceptions (19)

- The five Mahabhutas, gross elements, namely the earth, water, air, fire, and ether (24)

These tattvas are the evolutes of Nature. The Mahat (the Great One) is the first reality to emerge from Prakriti when sattva is predominant. Hence, it is also known as the Sambhuta (the manifested). It has a universal aspect as the intelligence of the world and a subtle aspect as the intelligence, buddhi, or the thinking mind in living beings. It is responsible for their rationality and discriminating awareness but remains mostly clouded due to the triple gunas. From Buddhi, ahamkaram, the self-sense, or the feeling of individuality, evolves and strengthens through desires and attachments induced by the gunas. It is responsible for the self-sense (ego) or the state of being (anavatva). From the ego evolves the brain or the memorial mind (manas), which is a repository of all perceptions, memories, and mental impressions and objects. Up to now, the tattvas we mentioned are subtle, but from here on, those we are going to mention are gross. They are the five senses (jnanedriyas), the five organs of action (karmendriyas), the five sense perceptions (tanmatras) or objects of the senses, and the five gross elements (mahabhutas).

They constitute the 24 tattvas. Together with Purusha (individual soul), who is an eternal reality, the number becomes 25. Nature uses them to produce the diversity in the world. Of them, Prakriti is without a cause. Mahat, ahamkara, and the five tanmatras are both causes and effects. The rest are effects only. Purusha is neither a cause nor an effect. It is eternal, without a cause and effect, and immutable.

The Natural evolution of things and beings, as suggested by the Samkhya, has many parallels with the modern theories of evolution. However, while modern theories focus mainly on the evolution of physical bodies and organs, the Samkhya doctrine proposes physical, mental, and spiritual evolution and transformation of beings over many lifetimes. Further, it views evolution, or the transformation of causes into effects, not as the miracle work of a Universal God but as a transformative process within Nature that progresses through different phases and in predictable patterns until the souls escape from the mortal world.

The Samkhya school was founded by Kapila, who probably lived in the Vedic period before the composition of principal Upanishads such as the Svetasvatara, Katha, Prasna, and Maitrayani Upanishads. The earliest known text of the school is the Kapila Sutras, or Samkhya Sutras, ascribed to sage Kapila (6th or 7th Century BCE), also considered the school's founder. However, we do not seem to have the original work. Our current knowledge of the schools is derived mainly from the Samkhya Karika of Isvara Krishna, who lived in the third or fifth Century ADE. Many commentaries on the Karika were written later on. Of them, the commentaries of Gaudapada and Vijnana Bhikshu are well known.

In the second chapter, the Bhagavadgita presents its own theistic version of Samkhya. It has a few features in common with the original school but is essentially theistic. While Samkhya recognizes Nature as the source of all creation, the Bhagavadgita identifies Brahman as the first cause of creation and Nature as a dependent reality, which manifests the worlds and beings under the will of God.

The second chapter of the Bhagavadgita, presented by Lord Krishna in the second chapter, has some similarities with the classical Samkhya but differs in many respects. However, it may be considered theistic Samkhya since it acknowledges Isvara, the Supreme Lord, as the source and controller of all, including the liberation of beings, and Prakriti as his dynamic and dependent aspect. While Classical Samkhya recognizes Nature as the source of all manifestation, the Bhagavadgita identifies Brahman as the Supreme Lord and traces all powers and manifestations to him only.

The Samkhya school is closely associated with the Yoga Darshana or the Yoga school of Hinduism. The Classical Ashtanga Yoga of Patanjali is modeled on the knowledge of the Samkhya and Yoga Darshanas only. The Yoga Sutras contains many references to Isvara, the individual soul, but makes no assertions about a supreme, universal Lord as the hub of all creation. The idea of Prakriti as the sole agent of creation and evolution probably contributed to the popularity of Tantras and the tradition of Shakti worship.

Impact on Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism

The Samkhya philosophy left a lasting influence on Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. While we do not know how far its doctrines found their way into them, it is possible that they might have found in its support for their own beliefs and practices. For example, Buddhism, Jainism, and several schools of Hinduism do not recognize the creator God. They also acknowledge the role of Nature in the manifestation of things.

In some respects, the Yogasutras of Patanjali is both an extension and an exposition of the Classical Samkhya and Yoga schools. The Samkhya yoga of the Bhagavadgita is but a subtle refutation of the fundamental doctrines of the Samkhya philosophy about Brahman or Purusha as the primary and efficient cause of all creation. However, interestingly, it accepts many concepts of the school, such as the division of the gunas and tattvas, the bondage of the embodied souls, the relationship between Prakriti and Purusha, the modifications of the mind, the binding nature of karma arising from desire-ridden actions, and the liberation of the jivas through yoga, renunciation, detachment, and self-transformation.

As in the Vedanta, the Samkhya school suggests that souls become bound when they are enveloped and embodied by Prakriti, and the resulting jivas fall into delusion and ignorance. When they realize that their attachment to Nature (the mind and body) and to worldly things is responsible for their bondage and that they are pure souls with an independent and eternal and indestructible existence of their own, independent of Prakriti and her tattvas and modes, they strive for liberation and achieve release or freedom from the cycle of births and deaths.

Suggestions for Further Reading

- The Samkhya Philosophy and 24 Principles of Creation

- The Bhagavadgita On The Problem Of Sorrow

- The Concept of Atman or Eternal Soul in Hinduism

- The Practice of Atma Yoga Or The Yoga Of Self

- The Problem of Maya Or Illusion and How To Deal With It

- Belief In Atman, The Eternal Soul Or The Inner Self

- Brahman, The Highest God Of Hinduism

- The Bhagavad Gita Original Translations

- The Bhagavadgita, Philosophy and Concepts

- Bhakti yoga or the Yoga of Devotion

- Hinduism And The Evolution of Life And Consciousness

- Why to Study the Bhagavadgita Parts 1 to 4

- The Triple Gunas, Sattva, Rajas and Tamas

- The Practice of Tantra and Tantric Ritual in Hinduism and Buddhism

- The Tradition Of Gurus and Gurukulas in Hinduism

- Origin, Definition and Introduction to Hinduism

- Hinduism, Way of Life, Beliefs and Practices

- A Summary of the Bhagavadgita

- Avatar, the Reincarnation of God Upon Earth

- The Bhagavadgita on Karma, the Law of Actions

- The Mandukya Upanishad

- The Bhagavadgita On The Mind And Its Control

- Symbolic Significance of Numbers in Hinduism

- The Belief of Reincarnation of Soul in Hinduism

- The True Meaning Of Renunciation According To Hinduism

- The Symbolic Significance of Puja Or Worship In Hinduism

- Introduction to the Upanishads of Hinduism

- Origin, Principles, Practice and Types of Yoga

- Hinduism and the Belief in one God

- Essays On Dharma

- Esoteric Mystic Hinduism

- Introduction to Hinduism

- Hindu Way of Life

- Essays On Karma

- Hindu Rites and Rituals

- The Origin of The Sanskrit Language

- Symbolism in Hinduism

- Essays on The Upanishads

- Concepts of Hinduism

- Essays on Atman

- Hindu Festivals

- Spiritual Practice

- Right Living

- Yoga of Sorrow

- Happiness

- Mental Health

- Concepts of Buddhism

- General Essays