What Stress Means to Most People

|| Abundance || Stress || Career || Communication || Concentration || Creativity || Emotions || Self-Esteem || Fear || Happiness || Healing || Intuition || Leadership || Love || Maturity || Meditation || Memory || Mental Health || Peace || Mindfulness || Inspiration || Negotiation || Personality || Planning || PMA || Reading || Relationships || Relaxation || Success || Visualization || The Secret || Master Key System || Videos || Audio || Our Books || Being the Best || Resources ||

Stress means getting upset about something.

Since stress means different things to different people, we need to get a firm handle on this slick term before we can make sense throughout the rest of this book. Effective communication of a concept requires that the particular terms used in the book mean the same to the reader as to the author.

Simply put, stress means getting upset about something. One’s peace and tranquility of mind are gone.

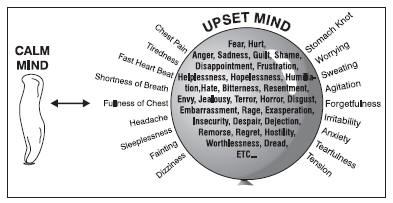

A stressed person is an upset person. He experiences one or more painful emotions, such as fear, hurt, sadness, anger, guilt, etc. in his conscious mind, in response to whatever has upset him. He is fully aware of these emotions. Because of their effect on his brain chemicals, he might experience some transient stress symptoms: irritability, sleeplessness, headache, poor concentration and the like. Once he has coped with the situation that has upset him, the painful emotions will disappear, he will calm down and his stress symptoms will go away. For example, one might become upset over losing his job. He might feel sad, hurt, fearful, guilty, ashamed and angry. He might experience many stress symptoms, such as sleeplessness, anxiety, tension, headaches and the like. After a while, he accepts the reality that people find jobs and lose them, lose jobs and find new ones. He calms down, gets another job and moves on with his life. The opposite of being stressed or upset is feeling calm.

We can compare the conscious mind to a balloon: when the mind is "inflated" with painful emotions, one experiences stress symptoms. When these painful emotions disappear from the conscious mind/balloon, it "deflates," or shrinks, and the stress symptoms disappear (see picture 1).

Picture 1: When painful emotions "inflate" the conscious

mind, stress symptoms appear.

Picture 1: When painful emotions "inflate" the conscious

mind, stress symptoms appear.

Rule #1: When painful emotions appear in the conscious mind/balloon, we experience stress symptoms. Conversely, whenever stress symptoms are present, the conscious mind/balloon is filled with painful emotions.

We can illustrate this point with following example: If there is sufficient smoke in the room, the fire alarm will go off. Conversely, if the fire alarm goes off, there must be significant amount of smoke in the room.

The conscious mind inflates and deflates with painful emotions day in and day out in response to numerous upsetting events and life problems. Even our dreams can upset us, inflating the sleeping mind with painful emotions and causing stress symptoms to appear. For example, if I dreamed of being chased by a ferocious bear I would be scared, my mind/balloon would inflate with fear and terror, and I would have several stress symptoms: fast heartbeat, shortness of breath, sweating, etc. Upon waking up, I would realize that it was only a bad dream. My fear would disappear, my balloon would deflate and I would calm down. The more upset we are, the more painful emotions we experience in the conscious mind; the more painful emotions we experience, the bigger the balloon becomes and the more we are troubled by stress symptoms.

Learning to keep the balloon shrunk is fundamental to coping with stress. Those who are unable to rid the conscious mind/balloon of painful emotions will experience more and more stress symptoms until the balloon pops and they come down with a stress disorder, such as depression or anxiety disorder. Then they will need a shrink to do the shrinking for them. Now you know why psychiatrists are called shrinks!

3. Stress symptoms are caused by painful emotions in the brain.

As we evolved into modern human beings over millions of years, we developed the ability to experience and express hundreds of painful emotions in response to upsetting situations. Thirty-six of them are responsible for bringing on many stress symptoms and disorders, and we will deal with those in some detail:

Fear, hurt, anger, sadness, guilt, shame, disappointment, frustration, helplessness, hopelessness, humiliation, hate, bitterness, resentment, envy, jealousy, terror, horror, disgust, embarrassment, rage, exasperation, insecurity, despair, dejection, remorse, regret, worthlessness, hostility, vengefulness, dread, sorrow, sinfulness, despondency, uselessness and powerlessness.

The presence of these potentially toxic, painful emotions in the conscious mind and brain causes the brain chemicals to change, resulting in the appearance of stress symptoms. In other words, pain in the brain is the basis of stress symptoms. The brain is connected to the body organs via circulating hormones and a vast network of nerves. Changes in brain chemicals are felt as changes in the functions of the body organs, such as the heart, lungs, stomach and skin. Stress symptoms are the brain’s way of warning us: "I am sensing many painful emotions in your mind. Get rid of them as soon as possible or do something to stop them from coming in." This is no different from a fire alarm going off when it detects more than the usual amount of smoke in the room.

The brain is hardwired to produce different groups of stress symptoms in response to different painful emotions. For example, fear and its cohorts in the brain produce a "fight or flight" response; sadness and related emotions produce stress symptoms related to "grief"; anger and allied emotions produce an "attack" type of stress response; and guilt and related emotions produce "guilty" behavioral responses. Readers interested in mastering the art of coping with stress must thoroughly learn about the nature of painful emotions, how they produce different stress symptoms and how to handle them. In other words, one must become emotionally savvy. In coping with stress, one’s Emotional Quotient (EQ) is more important than one’s Intelligence Quotient (IQ). We will study more about the nature of painful emotions in Chapter Four.

4. Stressors pump painful emotions into the conscious mind.

A. Sensory input. The conscious mind is constantly bombarded with information from the world around us. The five senses—seeing, hearing, touch, smell and taste—are conveyor belts that bring thousands of bits of information into the conscious mind/balloon on a daily basis. This continuous inflow of information is known as sensory input. The nature of most of the incoming information is neutral; that is, we feel neither good nor bad about it. For example, if you look at a chair, you feel neither good nor bad about the chair. Some of the incoming information is perceived by the mind as good, and we feel happy about it. For example, if you get a phone call from your boss telling you that he is pleased with your performance and is giving you a big raise, you will feel happy. Some other information is perceived by the mind as bad for us. For example, if you are told that your performance at work is not good and you could be fired from your job at any time, you will feel very upset. The upsetting situations are known as stressors.

B. There are two types of stressors:

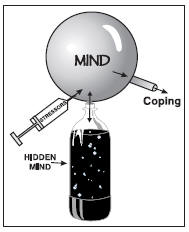

Picture 2: Stressors pump painful emotions into the mind.

Picture 2: Stressors pump painful emotions into the mind.

1. Bad events—such as the death of a loved one, the breakup of a relationship, betrayal or infidelity, an accident, robbery, assault, rape, the loss of a job, etc.—are extremely upsetting. They are one-shot painful events. When bad events occur, we experience many painful emotions in our conscious minds all at once, such as fear, terror, hurt, anger, sadness, guilt, shame and disappointment. The mind/balloon inflates suddenly with these painful emotions, and we experience severe stress symptoms.

2. Bad problems of life—such as problems with one’s job, money, health, relationships, etc.—are ongoing life problems. They upset us a little bit at a time, day after day, week after week and month after month. Often, we feel trapped in these bad problems. In this case, the mind/balloon inflates gradually, over a period of time, with painful emotions such as anger, fear, bitterness, resentment, insecurity, frustration or helplessness, and the stress symptoms are not as dramatic as when they are caused by a single bad event. If unsolved, most bad problems lead to the balloon popping because of the relentless buildup of painful emotions in the mind. When the balloon pops, one is brought down with a serious stress disorder, such as major depression or panic disorder.

C. The bicycle pump as a model for stressors. Since bad events and life problems pump painful emotions into the conscious mind/balloon, let us represent them as a simple bicycle pump. Bad events and bad life problems have something else in common with the pump: they both suck! We will read more about stressors in Chapter Five.

5. The hidden mind is like a soda bottle with fizzy soda inside it.

Picture 3: The hidden mind holds millions of bits of information

in its folders.

Picture 3: The hidden mind holds millions of bits of information

in its folders.

How does the conscious mind decide what is bad for it? The mind has a hidden compartment, like the basement of a house or the hard drive of a computer, where it stores a large amount of information that is gathered over a lifetime. The information pertains to whether an object or situation is good or bad for the mind: if it is bad, how bad, as well as how to react to it. As the powerful hard drive of a computer saves millions of bits of information in its numerous folders and files, this hidden compartment of the mind holds its own millions of bits of information. Every time the conscious mind receives some input from one or more of the five senses, it checks with the hidden mind by asking, "What is this? Is it good or bad for me? If it is bad, how do I react to it?" For example, if a stranger offered you a cookie, your conscious mind would ask your hidden mind, "Is this safe to eat?" Your hidden mind might say something such as, "You don’t know this person. The cookie he’s offered could be dangerous. Don’t eat it." This type of interaction takes place between the conscious mind and the hidden mind thousands of times a day. If your hidden mind does not know whether something is good or bad for you, your conscious mind will feel baffled or confused. A person whose hidden mind does not have the information needed to make the right decision in response to a piece of sensory input is said to be naïve, or innocent. We warn our naïve children about the dangers of the world by saying such things as, "Don’t talk to strangers! Don’t accept cookies from strangers! Don’t get into the car with strangers!"

The soda bottle is an ideal model for the hidden mind. We can compare the hidden mind to a full bottle of soda. Just as the dissolved gas in the soda is invisible until the bottle is shaken, all the information in the hidden mind is out of our immediate awareness until some sensory input activates it and brings it to our awareness. For example, right now, you are not thinking of President Bush—until you read his name. Immediately after reading it, your conscious mind might see his image on the screen of your mind, and you might experience neutral, good or bad emotions related to him. After a while, his image will disappear from the screen and go back into the "Memory" folder of your hidden mind. We will read more about the hidden mind in Chapter Seven.

6. Coping means shrinking the balloon.

Coping means getting rid of the toxic, painful emotions in the mind. This allows the brain chemicals to go back to their original position. Then the stress symptoms disappear. In effect, coping with stress simply means being able to shrink the balloon by appropriate methods. Coping requires us to become aware of the painful emotions in the conscious mind; get rid of them by expressing them; cancel them out by means of various mental skills; and skillfully turn off the pump by solving the problems that are hounding us. Then we calm down, and peace and tranquility return to the mind. It’s as simple as that—except that stressed-out people are not able to do any of these things. That is why they need a shrink to do the shrinking for them. Unfortunately, most psychiatrists these days attempt to control the symptoms of depression and anxiety by coating the balloon with drugs, rather than by shrinking it or teaching people how to shrink it themselves. Therefore, this book will focus on guiding the reader to shrink his balloon. We will read more about how to shrink the balloon in Chapter Thirteen.

Let us represent coping by a tube coming out of the right side of the balloon (see picture 4). Now the model of the mind is complete.

Picture 4: The model of the mind.

Picture 4: The model of the mind.

7. The model of the mind.

Let us briefly review the completed model of the mind. The bicycle pump in the picture above represents stressors. As soon as the conscious mind/balloon receives sensory input from the pump, it asks the hidden mind (soda bottle) about the nature of this input. When told, "This is bad," the conscious mind becomes upset. The balloon inflates with painful emotions, the brain chemicals change and stress symptoms appear. The side tube represents those actions that shrink the balloon. For example, if someone we love has died, the balloon will immediately inflate with painful emotions related to grief: sadness, hurt and sorrow. Inflation of the balloon will cause the appearance of severe stress symptoms: fullness in the chest, swelling of the face, intensely sad feelings. By grieving, crying, sobbing and expressing our emotions (using the side tube), we shrink the balloon and get rid of stress symptoms. Those who are able to keep the balloon shrunk all the time stay well.

The main idea of coping is that the output of painful emotions should equal the input. The reader must thoroughly understand this model of the mind and the interaction between its four components, to make sense of the various stress-related phenomena we will discuss in the chapters ahead.

Suggestions for Further Reading

- The Power of Determination

- Factors Which Contribute to Happiness

- Mental Maturity and Adult Behavior

- The Power of Your Thoughts

- To Think Outside the Box and Its True Meaning

- How to Avoid Stereotyping People

- Meditation and Levitation

- Enjoying the Simple Pleasures of Life

- 10 Reasons Why Plans Fail

- Thought, Energy and Manifestation

- How to Deal With Unpleasant Situations

- Stop Blaming Others

- Ten Effective Ways to Improve Your Self Esteem

- Determination, The Sustaining Power

- Are you Bored With Your Life?

- What Do You Think Success Means?

- Why People Worship Celebrities and Film Stars?

- Dealing with Adversity

- The Success Mindset

- Why Older Workers Find It Difficult to Get a Job?

- Invite Peace Into Your Life

- How to Practice Forgiveness in Daily Life

- Effective Listening Skills

- Being the Best - A Book on Self-help

- Think Success : Essays on Self-help

- Essays On Dharma

- Esoteric Mystic Hinduism

- Introduction to Hinduism

- Hindu Way of Life

- Essays On Karma

- Hindu Rites and Rituals

- The Origin of The Sanskrit Language

- Symbolism in Hinduism

- Essays on The Upanishads

- Concepts of Hinduism

- Essays on Atman

- Hindu Festivals

- Spiritual Practice

- Right Living

- Yoga of Sorrow

- Happiness

- Mental Health

- Concepts of Buddhism

- General Essays

Author:Reproduced with the permission of Dr. Bob Kamath, M.D. ©2007. All rights reserved. Graphics, Illustrations and Cover Art by Nikki Brown. Dr. Kamath, a Board Certified psychiatrist, has been in private practice in Cape Girardeau, Missouri since 1982. Dr. Kamath specializes in Stress and the psychopharmacological treatment of stress-related disorders such as depressive and anxiety disorders. He has been licensed to practice medicine in Missouri since 1977. To know more about him visit his website.